Few grape varieties divide the wine-drinking masses more than Pinot Grigio. The fact that it has been constantly struggling with a very public identity crisis benefits neither vine nor consumer. Not actually its own distinct variety, Pinot Grigio, like Pinot Blanc, is actually a color mutation of the much more universally beloved Pinot Noir. If Pinot Noir is a high-maintenance but friendly beauty who strives for perfection in all she does, Pinot Grigio is known as her plain, timid little sister who tiptoes through life trying her best not to get on anyone’s bad side. To make matters worse, she must follow in the footsteps of her earlier-born twin sister, the more sophisticated and worldly Pinot Gris. Despite all odds, however, Pinot Grigio managed in the early twenty-first century to find an accepting table in the lunchroom, where she has enjoyed popularity among an affable crowd ever since.

Few grape varieties divide the wine-drinking masses more than Pinot Grigio. The fact that it has been constantly struggling with a very public identity crisis benefits neither vine nor consumer. Not actually its own distinct variety, Pinot Grigio, like Pinot Blanc, is actually a color mutation of the much more universally beloved Pinot Noir. If Pinot Noir is a high-maintenance but friendly beauty who strives for perfection in all she does, Pinot Grigio is known as her plain, timid little sister who tiptoes through life trying her best not to get on anyone’s bad side. To make matters worse, she must follow in the footsteps of her earlier-born twin sister, the more sophisticated and worldly Pinot Gris. Despite all odds, however, Pinot Grigio managed in the early twenty-first century to find an accepting table in the lunchroom, where she has enjoyed popularity among an affable crowd ever since.

To understand Pinot Grigio, we must first understand its provenance. New grape varieties can come into existence in a number of ways–two existing varieties may be bred in a nursery, or cross-pollinated in the vineyard, or, sometimes, a new vine will turn out to have slight differences from its parent plant. If the vine grower finds the traits of the new plant to be desirable, he or she might take a cutting to propagate new, similar plants with the same characteristics, known as clones. With more than 1,000 registered clones, Pinot Noir is often considered to be a highly genetically unstable grape variety, but a more likely explanation for its clonal diversity is its ancient status. In existence for around 2,000 years, this grape variety has had more time than most to branch out and experiment. Pinot Gris made its first appearance some time around the early 1700s, popping up separately in Germany and France within just a year of one another. It finally found its way to Italy at the beginning of the nineteenth century, where it changed its name to Pinot Grigio and reinvented its personality.

Today, the Gris/Grigio divide can be a bit confusing. While they are indeed the same grape, they tend to present themselves quite differently. In France, Pinot Gris is at its best in Alsace, where it takes on the luscious character of ripe peaches and apricots, often with a hint of smoke, developing rich, biscuity flavors with age. However, as Pinot Grigio in north-eastern Italy’s Veneto region, the greatest achievement of these fresh and lightly fruity wines is being voted “least likely to offend.” Seriously: a Google search for the phrase “Pinot Grigio” yields 9,400,000 results, while the phrase “Pinot Grigio inoffensive” turns up 9,300,000. But how can a grape whose best attribute appears to be neutrality garner such praise in France, Germany, and Oregon as Pinot Gris? (It is worth noting that in the new world, lighter, more commercial, and inexpensive styles of this wine are typically labeled as ‘Pinot Grigio,” while the more serious, flavorful bottlings boast the name ‘Pinot Gris.”)

With certain practices in the vineyard and cellar, the Pinot Grigio grape can indeed produce wines worthy of higher praise than “inoffensive.” If acidity is preserved and yields as well as sugar levels are kept to a minimum, varietal character is given the chance to shine. Because the name “Pinot Grigio” alone is enough to sell wine to the general populace, most is produced by big companies that don’t feel the need to try very hard–hence the reputation. But with a bit of care and attention, the Italians are quite capable of coaxing bright and even complex flavors from the much-maligned grape. The region of Alto Adige does this with the most consistency, although some exciting examples are now coming out of Friuli Venezie-Giulia–Pinot Grigio’s best-known home–as well.

One of the best Friulian Pinot Grigios we have discovered is made by a winery called Scarpetta, owned and operated by Bobby Stuckey, M.S. and Chef Lachlan Patterson, the owners and masterminds behind James Beard Award-winning restaurant Frasca Food and Wine in Boulder, Colorado. Scarpetta’s wines are created to complement the Friuli-inspired cuisine of the restaurant, and they achieve this mission well. The Pinot Grigio, surprisingly, is the standout in their lineup, which also includes a Sauvignon Blanc, a Friulano, a Barbera, and a sparkling Rosé. Planting vines in cooler sites accounts for impressive balance of acidity and alcohol, and a brief period of skin-contact followed by six months of lees aging lends body and texture atypical of the often watery beverage.

On the nose and palate, this wine is anything but bland, with aromas of white flowers, peach, apricot, and hints of minerality. Dry and crisp, with just the right amount of acidity, flavors of stone fruits, lavender, honey, lime, melon, pear, white flowers, and minerals make this Pinot Grigio perfect to drink on its own: refreshing, but never boring. Naturally, a wine created by restaurateurs is going to make for some great food pairings as well–try it with proscuitto, sashimi, and lighter dishes based on chicken, fish, and pork.

To all of the Pinot Grigio nay-sayers out there: we suggest you give Scarpetta a try. And for the already initiated, this will be an easy way to step up your wine game and see what this oft-underachieving grape is capable of at its best. If you’ve spent your life shunning Pinot Grigio, make a space at your lunch (or dinner) table. You just might find that you’ve been a bit judgmental without really getting to know her.

2012 Scarpetta Pinot Grigio Delle Venezie IGT, $16

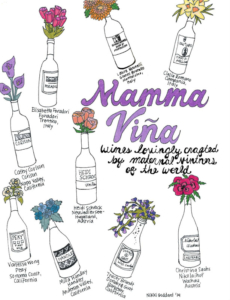

Crafting a great bottle of wine can be quite similar to raising a family. From shielding sensitive young grapes in the vineyard from pests and disease to controlling unruly fermentations in the cellar, certain winemakers already know that the process of growing up depends on both nature and nurture. This Mother’s Day, celebrate the mothers in your life with a glass of wine made lovingly by a winemaker who is also a mother.

Crafting a great bottle of wine can be quite similar to raising a family. From shielding sensitive young grapes in the vineyard from pests and disease to controlling unruly fermentations in the cellar, certain winemakers already know that the process of growing up depends on both nature and nurture. This Mother’s Day, celebrate the mothers in your life with a glass of wine made lovingly by a winemaker who is also a mother.