We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

– Joan Didion

I’ve been thinking about what to say during the pandemic when someone walks into the shop and asks what wine they should drink with dinner.

Something different, I say, as “different” seems to describe most of our lives right now, and I think most of us want something different because we want at least that consistency.

The Central Paradox

It seems to me that we are sharing the experience of the pandemic, but we often feel alone. So open that bottle of Pommard, Gevrey-Chambertin, or Barolo you’ve been saving and sit on your porch–if the Air Quality Index allows–and open it. Say hello to the neighbors you didn’t know you had.

I’ve been thinking about what words to use to tell you…

…that the wine you drink today will chart more than your future. That each bottle you drink and think about will give you more language. That you’ll be able to talk about Rothko and the Faiyum mummy portraits.

Pavane

Silence is a shape that has passed.

-Wallace Stevens

Every glass is a shape, a still life, a piece of music, the curl of green in the tree outside your window. The last plum.

What Do We Really Want to Talk About When We Talk About Wine?

We want, it nearly always seems, to talk about love or the garden. Or the moon dervishing in her scarves.

Say…

…you’re at my house for a dinner party. We’re on the deck. It’s about 7:15, and the Champagne is, sadly, though not tragically, nearly gone. And while everyone is enjoying it, some of us are sort-of-secretly hoping a brave soul will socially distance the bottle and save the remaining third until we’ve had time to try the trousseau. Surely, the Champagne will taste different after a glass of snappy fall-fruit red from the Jura.

…you’re at my house for a dinner party. We’re on the deck. It’s about 7:15, and the Champagne is, sadly, though not tragically, nearly gone. And while everyone is enjoying it, some of us are sort-of-secretly hoping a brave soul will socially distance the bottle and save the remaining third until we’ve had time to try the trousseau. Surely, the Champagne will taste different after a glass of snappy fall-fruit red from the Jura.

I never want to get in the way of anyone’s enjoyment, but too often we don’t try out new ideas, or revisit old convictions. Making alterations in our accepted patterns seems especially important during these times because we might find better solutions or even see problems for the first time.

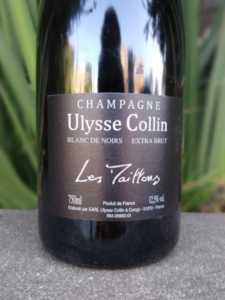

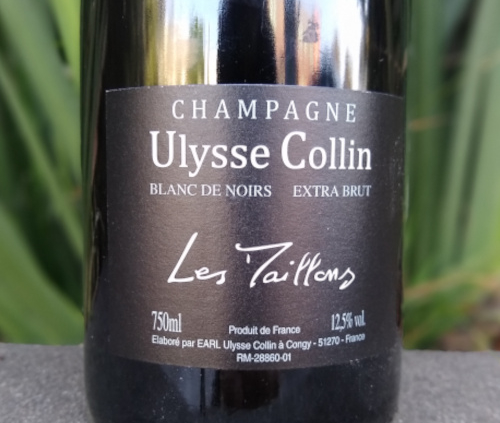

So why not save the Champagne for a while and see how it goes with the entrée? Or–open a bottle of Ulysse Collin’s Blanc de Noirs ‘Les Maillons’ Extra Brut NV Champagne to go with that piece of grilled rib eye.

Explanations (i)

The drinker is part of the wine. Q. E. D.

Explanations (ii)

We tell ourselves stories because we need to follow a narrative to make sense of the weeks; we tell ourselves stories because we need to lie to ourselves to deal with the pandemic, the fires, the inevitable shifts in our country’s foreign and domestic policies.

since feeling is first

We want, it so often seems, to say what we’re thinking. It takes practice to articulate what our bodies want.

A Lakeside Cabin

All worthwhile subjects exist in part and in paradox.

The less we understand about a subject, the longer the conversation can be about that subject. That’s a good thing. We want to talk about things we want to understand more about, like wine, cosmology, or the price of furniture–though the letter involves rickety logic. Each bottle is its own story, its own beginning, seemingly isolated but sipped along the same shore, our toes trailing the cold clear water.

Explanations (iii)

We are at times only essence.

Two Concepts to Help You Learn About Wine

- There is a relationship between what you know and what you like.

- It is the strangeness of Goodnight Moon that appeals most.

What We’re After, After All

An accurate application of language to experience. Something new, perhaps? A glass of kadarka or jacquere? Lamb chops at 1:00 AM?

[Stay tuned for Part II of this essay, coming next month.]

A somewhat newer producer to me, from the town of Pachino just south of Siracusa, is

A somewhat newer producer to me, from the town of Pachino just south of Siracusa, is  COS

COS