-Emilia Aiello

Women winemakers are not a new phenomena, but in the last few years as I deep dive into my own area of interest and expertise (southern Italy), I have noticed a curious commonality in emerging wine regions: women.

Italy is well established on the wine map, but certain regions remain obscure. You know where Rome is, but what about Lazio, the entire region that surrounds the ancient city? As of late, Lazio is gaining momentum. Perhaps the hype has yet to reach the United States, but in Italy the region is putting on numerous tastings each year to highlight the local producers and grapes— Lazio is hyping up Lazio. Initially, creating interest in the local area is more important than abroad as working the local community inevitably works the local economy. My eyes were already on Lazio when I worked as the wine director at a Roman osteria in New York City, but before I tasted the wines of Maria Ernesta Berucci I had yet to really experience great Lazio wine. Her vini had an entirely new character— wild and bright, with a depth of flavor I had noticed only a handful of times in my youthful career. The wines intrigued me so much that I decided to meet Maria Ernesta on her own turf (vineyards) in Piglio. I met a woman so immersed in her work that it had no separation from her life. Not as as workaholic, but rather someone who applies the same ethos and dedication to their work as they do to their overall way of living. I also discovered that Maria Ernesta is well integrated in her community, aligning herself with vignaioli (winegrower in Italian) who follow similar principles. She shows up at every community tasting event and is part of Ciociaria Naturale, a coalition of small producers from a very specific part of Lazio whose goal is not just to make good wine, but to foster community and pride in an otherwise energy-barren region.

Once in tune to Maria Ernesta, my palate was primed to taste wines differently. I began to look to other regions of Italy ramping up— who was behind this energy shift, and why now? In Abruzzo, for instance, women are emerging as some of the brightest talents (Tiberio, Ciavolich, and Emidio Pepe‘s granddaugher, Chiara is officially taking over the winemaking side). Their wines are amazing, but in a particular way. Similar to the story of Maria Ernesta in Lazio, their total immersion in their work and ability to incorporate their business skills with their agricultural and winemaking prowess are bringing hype to the region among consumers and the younger local generations. Women are often at the forefront of social movements and change, and it seems that the wine industry is no outlier.

I suppose it would now make sense for me to give you an exposé on the aforementioned names and wines, but my story is not finished. These women inspire me to step outside of my comfort zone, and I am following the breadcrumbs to other regions and winemakers that make wine with this particular energetic charge. Paul Marcus Wines gives me the space and privilege to taste and learn about pretty much every wine region of the world. Amazingly, that energy and wild nature that I first experienced tasting Maria Ernesta’s cesanese wine from Lazio, is a throughline in particular wines made in other countries, regardless of grape and terroir. My theory is perhaps now clear. Of course, I am not claiming that only women are capable of making charged vino, but rather it takes a certain investment—winemakers that have fully bought in to what they do and who view grape growing and winemaking as a way of life. I just happen to notice this approach is more prolific among women.

For Women’s History Month I chose two women trailblazers who are not Italian, that have opened up my mind and taste buds to new possibilities. They successfully weave in their own imaginations and experience to create wines that are somehow equally wholly unique and timeless classics.

Terah Bajjalieh of Terah Wine Co.

Terah Bajjalieh is a winemaker and consultant from California. A native Californian with Palestinian roots, Terah refined her unique style and found her love of wine by way of food and from her travels across the globe. She started her professional career in the hospitality industry studying at the International Culinary Institute in California. She then spent time working in wine bars, a Michelin-starred restaurant, wine education, and consulting in the Bay Area. The next step for Terah was to ambitiously immerse herself into the international world of wine, studying Enology and Viticulture in both Spain and France. She has completed 13 harvests in five countries: Meursault (France); Barossa Valley (Australia); Marlborough (New Zealand); Mendoza (Argentina); Sierra Foothills (U.S.); Sonoma (U.S.); Napa Valley (U.S.); The Willamette Valley (U.S.).

The California wine climate is shifting and while the days of big house cabs and zins are still here, they have moved aside to allow for more diversity in grape variety and winemaking. Terah’s philosophy comes from years of experience and experimentation. She focuses on lesser known California growing areas as well as Mediterranean grape varieties. Her wines are a pure and expressive blend of CA climate, Mediterranean vibes, and Terah’s kind and discerning personality.

2023 Falanghina Skin Contact Orange (Lost Slough Vineyard in Clarksburg)

100% Falanghina, native to the Sannio area of Campania, Italy

Situated in the heart of the Clarksburg AVA, this growing region benefits from the cool breezes that flow from the Sacramento River Delta. Combined with the rich sandy, clay loam soils, it is an environment that is optimal for producing exceptional wine grapes. The maritime influence tempers the region’s warm days, allowing for slow and even ripening, which preserves acid and results in wines with incredible freshness.

100% destemmed and fermented on skins through primary fermentation for 12 days. This process allows the grape skins to impart color, flavor, and texture, resulting in a wine with enhanced complexity and character. Pump-overs were performed during the maceration period, and fermentation naturally commenced due to the wild yeast and native bacteria. These techniques ensured even extraction of flavors, and tannins from the skins, promoting a harmonious integration of elements. The wine was aged on fine lees for 10 months in stainless steel. Unfined and unfiltered to preserve texture and integrity.

Crisp notes of freshly picked green apples and vibrant citrus peel intertwine with more intricate layers of brioche, dried apricots, and honeyed figs. Chewy tannins with long-lasting minerality. This is a very approachable orange wine, with zero funk. Think of it more like a rich white when you choose your food pairings: hard cheeses; hearty roast chicken dishes; al pastor tacos.

2024 Terah Wine Co. Vermentino (just bottled/new release!)

100% Vermentino

The vermentino grape’s origins are unknown, with Spain, France, AND Italy claiming native rights over the variety. Regardless of its true origin, it is 100% Mediterranean. 2024 was just bottled four weeks ago and is making its debut with Paul Marcus Wines. The classic subtle peachy stone fruit, fresh cut grass, lemony zing is reminiscent of a Corsican version, while the palate has an oily/silky feel more akin to Sardegna’s blueprint. I suppose what we are tasting is the richness of the California climate and fertile soils, combined with Terah’s unique ability to coax out the grape’s vivacious acid and minerality.

Sarolta Bárdos of Tokaj Nobilis

“Sarolta is one of these people who is constantly and seemingly unconsciously sampling herbs, smelling blossoms, inspecting leaves and so on. Her palate isn’t just shaped and informed by the grapes, but everything surrounding them”– Eric Danch

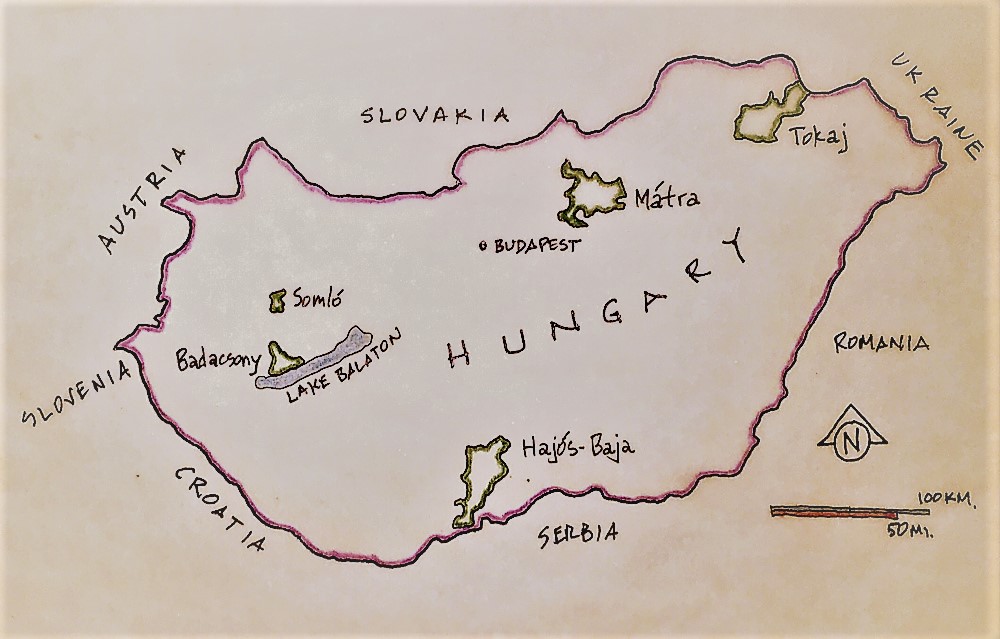

Hungary is not a country that first comes to mind when we list off the great wine regions of the world, though the sweet Tokaji wines made from Hungary’s native furmint grape is one of the most reputable sweet wines of the world. It remains as the country’s flagship wine and the only testable Hungarian wine on the blind tasting portion of certified sommelier exams*. So what about the region’s other varieties and wines? While they do not totally remain in oblivion, they are so obscure we really only source them from one importer here in California, Danch & Granger.

Tokaj, Hungary has an extraordinary number of women winemakers. According to Eric Danch, importer and our de facto Eastern European wine guru, the reasons for this are varied: since sweet wines were historically the most important wine, it’s often cited that women had a better sense of sweetness and therefore when to pick the grapes. Out of practicality, they found themselves in the cellar tasting as well. Another potential impetus could be that during the communist period, men were obligated to go out and work, leaving the women at home to tend to the family, cook, and make the house wine.

Born and raised in Tokaj, Sarolta Bárdos possesses a keen awareness of the changes and challenges facing the region. Beginning her career studying at the University of Horticulture in Budapest, she took advantage of the recently fallen Iron Curtain and spent time in France, Italy and Spain. Upon returning to Hungary, she worked at Gróf Degenfeld and soon after became the inaugural winemaker at Béres Winery in nearby Erdőbénye overseeing 45 ha of vineyards. Preferring closer attention to detail and the total knowledge inherent in small-scale winemaking, she left and planted her own 6 ha in 1999. In 2005 she converted a traditional 19th century house into a winery and cellar in the middle of the town of Bodrogkeresztúr. All sites are worked by hand, certified organic, and rely mainly on plant extracts, orange oil and sulfur. The wines embrace a myriad of volcanic soils with remarkable aromatics and balanced acidity.

2019 Tokaj Nobilis Barakonyi– fully dry

100% furmint

Underbrush. As if a warm breeze just rolled through kicking up a chalky/dusty whiff. Subtle oak spice with rich caramelized pineapple and lemon curd notes on the palate, offset by high, mouthwatering acid. I usually don’t like comparing unique wines and grapes to more recognizable, pricey regions. My concern is that I will take away from the obscure wines’ unicorn vibes, but to give you an idea of what kind of value this is for the quality: think southern Burgundy (chardonnay) but with riesling** acid. What impresses me more than simply the high quality of the wine is that Sarolta achieves it via minimal intervention techniques. This wine is made from more than organic grapes— she uses orange oil in the vineyards, for Bacchus’s sake! In the cellar, it is fermented with wild yeasts, has very minimal sulfur additions, with no fining, clarification, or filtration.

*for sommelier exams and blind tasting, there is a list of grape varieties made into certain styles of wines from various regions that the examiner is allowed to present to the examinee. This list does expand and change as our collective knowledge and curiosity grow beyond French appellations and “classic” grape varieties. But to give you an idea of how slow the process is of allowing more wines into the blind tasting exam, the only testable Italian red wines are Barolo made from the nebbiolo grape; and Brunello and Chianti Classico made from the sangiovese grape (Italy boasts over 400 documented native varieties). The sweet Hungarian Tokaji wine has been on that codified list since the inception of the certification exams and remains the only wine from Hungary allowed on the tasting portion of the exam.

**furmint and riesling share a parent grape, Gouais Blanc.