An oxymoron? Mutually exclusive? Magical thinking? No, affordable Burgundy really is a thing.

Of course, it is nearly impossible to buy a quality bottle of Gevrey-Chambertin or Puligny-Montrachet for $30 or $40. But improvements in winemaking (with perhaps an assist from climate change) have dramatically increased the quality of wines from less-renowned areas of Burgundy. And though we now taste many fine examples of pinot noir and chardonnay from a wide range of locales, Burgundy remains, for many of us, a unique delight and still provides the greatest expressions of these two grapes.

Here are a couple of whites and reds between $20 and $50 that exhibit the distinctive pleasure and beauty of excellent Burgundy without breaking the bank. Fair warning: They may whet your appetite for some of those more special-occasion wines previously mentioned.

Whites:

2019 Seguinot-Bordet Petit Chablis ($21)

The young and talented Jean-François Bordet comes from a family that has been making wine in the area since the 1590s (19 generations). The wine is classic–vibrant, lively, and textured (but no oak), boasting the distinctive, sea-fossil minerality that makes Chablis and Petit Chablis so unlike any other chardonnay from Burgundy or elsewhere.

2016 Marc Colin Saint-Aubin 1er Cru ‘Les Castets’ ($49)

For now, the Saint-Aubin appellation–nuzzled up next to Meursault and Chassagne in the southern part of the Côte de Beaune–still flies under the radar of many Burgundy lovers, but don’t expect that to continue for much longer. Here’s what Marc G. had to say after recently enjoying a bottle of the 2016 Colin: “After opening with a hint of reduction, it blossoms into an immensely satisfying, superbly balanced combination of fruit and freshness. Grab your crab crackers, and go to town!”

Reds:

2017 Maurice Charleux Maranges 1er Cru ‘Les Clos Roussots’ ($33)

This jewel comes from one of our great longtime friends, Charles Neal, who imports a remarkable selection of wines from France that just about always offer an exceptional price-to-quality relationship. (He’s also written a definitive book about Armagnac and remains a knowledgeable and gifted music writer.) Maranges is the southernmost appellation in the Côte de Beaune and is beginning to enjoy recognition as an area that delivers first-rate, generously flavored wines deserving of greater attention. Les Clos Roussots is a parcel from south/southeast vineyards at about 1,000 feet. It is a delicious example of the lush, full-fruited wines of the area. All of the Charleux wines are worth seeking out, including the newly arrived 2017 Santenay 1er Cru ‘Clos Rousseau’ ($36), made from 30-year-old vines and offering a touch more minerality from the limestone soils.

Given the prices of Burgundy, it’s rare that I can say, “We have trouble keeping this in stock.” But that has been the story with this wine–multiple customers coming back for multiple bottles, or cases. Mercurey, in the Côte Chalonnaise, south of the Côte de Beaune, can produce wines of great strength and character that bear a resemblance to Pommard. So far, 2018 is proving to be a lovely vintage for red Burgundy, and this charmer from Faiveley shows what both place and vintage have to offer. It has classy, expressive, upfront fruit notes that make the wine immensely appealing right now, but also enough backbone and grip to let you know that there is more to be revealed with another few years in the bottle.

As always, keep an eye out for exciting new arrivals over the next few months, especially as more of the stunning 2018 reds start rolling in. For instance, we’re awaiting the 2018 Auxey-Duresses from organic grower Agnes Paquet, a darling of the three-star Michelin somms in France. Also new in the shop is the 2018 Domaine des Rouge-Queues Santenay ($49), a dark-fruited, earthy, yet supple pleasure.

Everyone at PMW loves Burgundy, and we strive to curate our selections very carefully to offer attractive options from various climats–and at a range of prices. At the highest level, Burgundy can be an almost otherworldly experience (in more ways than one). But thankfully, we can defy some conventional attitudes about the area and show that reasonably priced, quality Burgundy is not a fantasy.

A somewhat newer producer to me, from the town of Pachino just south of Siracusa, is

A somewhat newer producer to me, from the town of Pachino just south of Siracusa, is  COS

COS

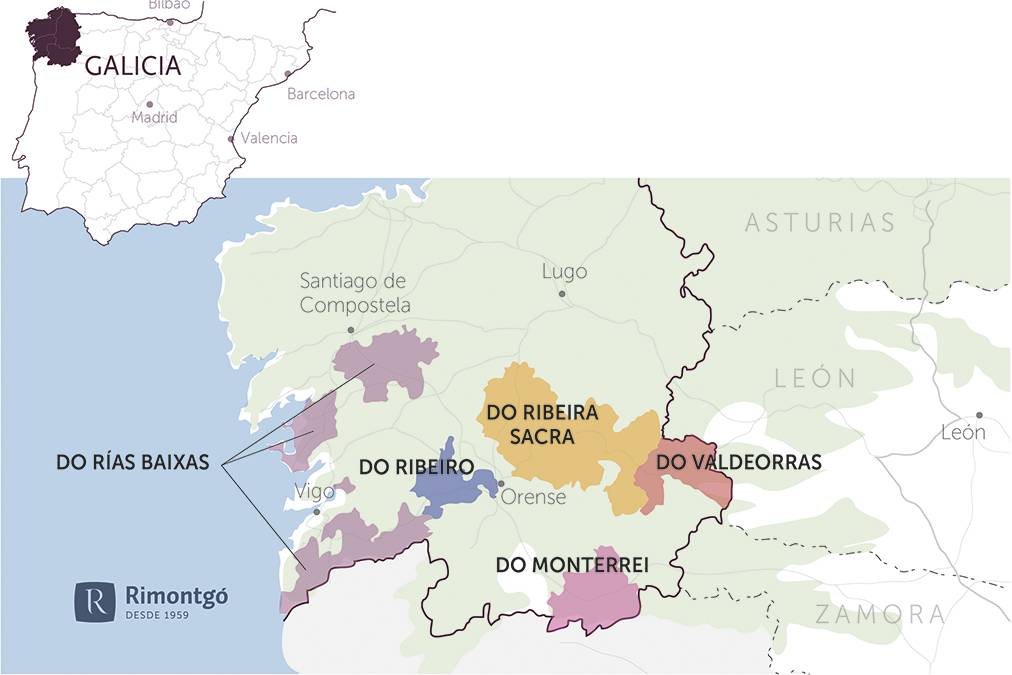

Among the leading lights of Ribeiro is Luis Anxo Rodriguez Vazquez, who has been making wines in the region for more than 30 years. Included in his lineup are two treixadura-based cuvees, both available at Paul Marcus Wines. Viña de Martin Os Pasás blends treixadura with lado, albariño, and torrontes, and it’s aged in steel on the lees for 10 to 12 months. It makes a perfect match for simply prepared fish and chicken dishes, as well as a variety of hard cheeses. A Teixa adds godello and albariño to its treixadura foundation and spends a year on the lees in large wooden vats. This cuvee partners brilliantly with all manner of shellfish (especially scallops) and full-flavored poultry creations.

Among the leading lights of Ribeiro is Luis Anxo Rodriguez Vazquez, who has been making wines in the region for more than 30 years. Included in his lineup are two treixadura-based cuvees, both available at Paul Marcus Wines. Viña de Martin Os Pasás blends treixadura with lado, albariño, and torrontes, and it’s aged in steel on the lees for 10 to 12 months. It makes a perfect match for simply prepared fish and chicken dishes, as well as a variety of hard cheeses. A Teixa adds godello and albariño to its treixadura foundation and spends a year on the lees in large wooden vats. This cuvee partners brilliantly with all manner of shellfish (especially scallops) and full-flavored poultry creations. Another producer working wonders with treixadura is Bodegas El Paraguas, whose estate white blend is mostly treixadura with some godello and albariño. With minimal oak influence (only the godello sees wood), the El Paraguas is a bit more focused than Rodriguez’s blends, and equally as satisfying.

Another producer working wonders with treixadura is Bodegas El Paraguas, whose estate white blend is mostly treixadura with some godello and albariño. With minimal oak influence (only the godello sees wood), the El Paraguas is a bit more focused than Rodriguez’s blends, and equally as satisfying. Rodriguez makes two brancellao-based cuvees (blended with other indigenous Ribeiro grapes including caiño and ferrol) that have been featured at Paul Marcus Wines: the Eidos Ermos bottling, which combines oak and steel aging, and the slightly sturdier A Torna Dos Pasás, which sees 12 months of used oak. These food-friendly blends can accompany anything from spicy pork dishes to tuna steaks.

Rodriguez makes two brancellao-based cuvees (blended with other indigenous Ribeiro grapes including caiño and ferrol) that have been featured at Paul Marcus Wines: the Eidos Ermos bottling, which combines oak and steel aging, and the slightly sturdier A Torna Dos Pasás, which sees 12 months of used oak. These food-friendly blends can accompany anything from spicy pork dishes to tuna steaks.