Excavation

artifact / ärdəfakt /

noun: an object made by a human being, typically an item of cultural or historical interest.

archeology / ärkēˈäləjē /

noun: the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains.

Experience

Wine can represent many things, like a particular flavor, a palatal experience, the time and efforts of cultivation, or the intellectual design of a product. And we can talk about it in so many ways too, evaluating wines geographically, aesthetically, linearly, horizontally. We use metaphor. We use qualitative biochemical data. We use narrative, and we attach it to a physical object destined for consumption, consume it, and begin to evaluate based on an array of potential methods of inquiry. If we are to treat the appreciation of wine in any academic way, that is to study it, we first must choose the method and scope of inquiry, which for me, particularly regarding older bottles, skews to the archeological.

Throughout my time at Paul Marcus Wines I was fortunate to taste, with some regularity, wines that far surpassed me in age and maturity. Over the past few years I’ve seen a surge in interest, enthusiasm, and availability of more obscure wines like this (18 year-old Sancerre Rouge, 28 year-old Portuguese Arinto, 30 year-old Santa Cruz Cabernet), wines that have taken on the secondary and tertiary characteristics of graceful development. Right away you can recognize acidity and color, defining characteristics of longevity, the ability to stay fresh, and the availability of concentrated fruit. But always, wines like these come with a caveat, a disclaimer of sorts about provenance, about transportation, storage, preservation, the guarantee on untainted products, the artifacts we so casually imbibe. So what can the study (and appreciation) of these agricultural remains signify about history? Perhaps that it inevitably devours itself.

Vineyard at Villa Era, Alto Piemonte

Visiting Piemonte

Last November, I was invited to Italy by the business consortium and viticultural association of Beilla, a small sub-region of the Alto Piemonte, west of Milan and almost to the Alps. It is an absolutely beautiful area, richin chestnuts, risotto, and an earnest wool milling industry. Right now, the region is in the process of redefining itself as a premium growing and production zone for grapes, particularly Nebbiolo. Today about 1,500 hectares of vines are planted in Alto Piemonte, primarily to Nebbiolo, though small amounts of Vespolina, Croatina, Uva Rara and Erbaluce are also planted. In 1900, however, over 40,000 hectares of grapes filled the region, a gross historical disparity which the winemakers there hope to resolve. The cool temperatures, extended sunlight exposure from altitude, latitude, and proximity to the Alps, and the geological event in which a volcano upended a mountain to expose ancient marine soils, all contribute to the severe minerality, acidity, and vivid coloration and red flavor of these Nebbiolo wines. Although the Langhe in the more southern part of Piedmont carries more commercial and critical weight in the industry now, the sheer volume of wine produced in the heyday of Alto Piemonte, and the evaluative quality of that wine, can shed light on both the cultural and natural history of the area. Touring vineyards and wineries, attending a seminar on soil types, tasting recent releases of wines from a dozen Alto Piemontese producers, and eating beautifully from the local farms and tables were all illuminating aspects of the culture and the cuisine and the heritage of the region, but nothing taught me more than tasting through a series of library bottles from four small wineries. It was easily the most personally revealing experience I’ve ever had with wine.

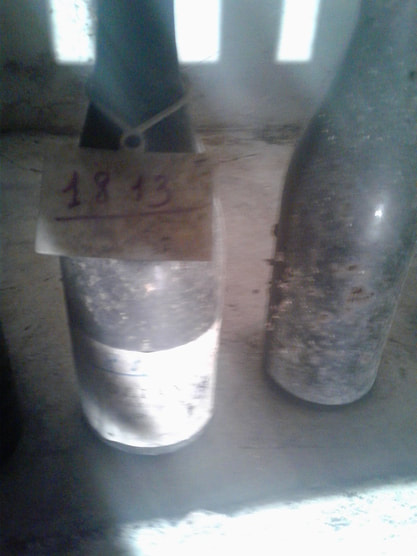

Before the tasting at Villa Era, a tiny producer in midst of laborious reclamation of vineyard sites from a century or so of forest encroachment, we toured the cellars (as we had the previous evening at Castello di Castellengo) to see the dusty, cobwebbed and moldy bottles of mismatched shape and size with tags and decomposing labels that date these artifacts through the past several centuries. These library collections of estate bottlings provide evidence that throughout time the properties yielded a product worth preserving in glass, underground in stable conditions, on the assumption that someday, someone would recognize that this was a fine wine designed to shine for future generations.

Bottles in the cellar at Villa Era, Alto Piemonte

Experiencing Aged Piemonte

The oldest artifact was a bottle of 1842 Castello di Montecavallo which is almost impossible to describe ingesting other than physical euphoria a, sensation of emotionally charged discovery. To share this piece of completely vibrant, assertive history, with the current generations of folks who farm the same land produced in me this neurological firing where I tried to connect pure sensory experience with the particular circumstance and somehow try to intellectually remember that this wine was deemed over the course of 175 years to be worth preserving, and that this gorgeous and completely unexpected semi-sweet but citric and lively wine five times my age was now going to be absorbed by my body. It felt as though I’d consumed an ephemeral dose of wisdom.

I know that’s hard to qualify. But trying to compare, or at least comprehend, the 1896 Castellengo and 1897 Villa Era was somewhat more grounded. I’d been in these cellars, walked in these vineyards; I was sitting in the building where 120 years earlier one of these wines had probably just finished fermenting, maybe just gone into barrel. One was reddish and slightly tannic, the other golden and slippery, and both were fresh. So you speculate. The grape, the vintage, the design? Two wines made a year apart within ten kilometers of each other and yet so fantastically different. And still with this surreal recognition that these wines were made around the time that my ancestors left Europe to participate in a different history a continent away.

Tasting a pair of wines, 1931 Montecavallo and 1934 Castellengo, I could sense some greater intensity, whether to do with process development or a renewed artisanal concentration in the wines after the industry fallout in the first decade of the 20th Century due to climate and disease, I don’t know. But the Montecavallo, like the 1842, offered a pure, sandy, pear-like quality, and the Castellengo, like the 1896, was denser, richer in color. The 1934 showed great definition as Nebbiolo, herbal, brilliant red, tannic and tough like a the skin of a wizened crabapple, a gorgeous wine and my favorite of the entire tasting.

Modern Respects

The more recent presentations, a 1960 from Villa Era, and a 1965 and 1970 from Tenuta Sella, a producer PMW has recently carried, proved a welcome familiarity, more within the bounds of my previous experience. These were wines with structure, ripe and dusty fruit and emphatic texture. These were wines wound with youth, wines that I expected to develop further. In the Sella wines, particularly, a continuously operating producer since the 17th Century, I tasted exuberance, a great and yet unrevealed potential. I felt aligned with Nebbiolo, a tart little corner of recognition on my palate, but I also felt the resonance of timbre, a uniformity, or at least a seam of connective tissue that stitched me to the place, to the people, to the things this circumstance in time and culture had revealed.

Tenuta Sella 1965 Lessona & 1970 Lessona

And then after sharing a bottle of the 2010 Sella Lessona over dinner back in California, and talking and laughing and telling the story, exposing the narrative and presenting the evidence, one can still only project the future. We have what we have and we have what has been preserved and with that we have to make do. I know that in Alto Piemonte they used to make great wine and that over time the wines changed and adapted and that now by looking back, it is also possible to look forward, to understand the history and prehistory of a specific place, the culture of past, present and future through artifacts.

(credit: Patrick Newson)

Wine Parties: A Guided Wine Tasting

TastingWhat Is A Guided Tasting?

In the interest of sharing my passion for the broader world of wine with the people close to me, I decided to have a group of friends over for a guided wine tasting – that is, one in which one person (me in this case) guides the discussion and helps draw out responses from everyone. My goal was to share a bit of my knowledge and to help my friends understand better what exactly they’re getting when they order a bottle of wine in a restaurant or bring one home from a store. And as Mark said in our previous newsletter, “the goal, as in other kinds of parties, is good conversation and good times spent with good friends.” I wanted my tasting to be fun and not to get bogged down in formalities.

Choosing Your Theme

I had come up with several ideas for tastings, including one that focused on the formal techniques of wine tasting. One evening over dinner, I bounced my ideas off my partner. He’s a valuable resource in this discussion, since he has a good knowledge of wine but doesn’t take it too seriously. His suggestion seemed like the best: a comparison of common California wines and their French counterparts. The idea was to analyze how differences in climate, wine making, and culture can affect what’s in the glass – a conversation that sounded fun to me. This kind of tasting also would give me a chance to clear up the mysteries of French wine labels and help folks get an idea of just what expect from a particular bottle of French wine.

To Blind Taste or Not?

With this theme in mind, I decided to make it a formal, blind tasting of four reds and four whites. I chose Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon for the reds and Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay for the whites, with a California and French example of each of the four types. I chose to do the tasting blind (i.e., with the bottles in paper bags to cover up the labels) so that no one would be tempted to jump to conclusions based on any preconceived opinions in favor or against either California or French wines.

Having chosen a theme and format, I invited four couples over for an after-dinner wine tasting party. That made the total ten people, an ideal number, and with various prior engagements, the group whittled itself down to eight. I offered to supply all eight wines and to host the party at my house, asking others to bring some snacks to munch on while tasting. (Bread, cheese, and pâté are great to have on the table with a tasting – they help clear the palate and put something in your stomach besides wine.) I also borrowed some glasses from a co-worker. The idea was to do two flights of four wines – first the whites and then the reds.

I had the luxury of 64 small wine glasses (8 per person), but it would be possible to do this kind of tasting with 32 (4 per person) or even 16 (2 per person). In the latter case, you’d simply taste the wines in flights of two rather than four.

Keeping Conversations Going

I put a lot of thought into how to facilitate the conversation. I wanted to avoid my tendency to get too pedantic, knowing that no one wanted a lecture. But I also wanted to make sure that there was at least some serious discussion about the wines. I figured the best way to facilitate discussion was to minimize my spiels and ask everyone else questions. There are a few basic questions to ask when tasting wine that can help you start to make distinctions:

Providing Common Ground

I’ve experienced firsthand that dazed expression in other people when I start using language to describe wines that is routine to me. I wanted to avoid the pressure that people feel to come up with “good” descriptors and instead ask everyone to say in their own words what they thought of the wines. These basic questions provide a framework for discussion while allowing each person to respond to and talk about the wines in an individual way.

As my guests arrived, I assembled the wines in the kitchen, opened them, and smelled them to make sure that none of the bottles was corked. I put each of the bottles in a brown bag and wrote a letter on the bag (A through H) so that we’d have a way to refer to the wines as we talked about them.

Starting With Whites

Starting with whites, I poured two Sauvignon Blancs, 2001 Honig from Napa ($12.99) and 1998 Château Reynon Blanc from Bordeaux ($11.99), followed by two Chardonnays, 2000 Handley Anderson Valley from Mendocino ($15) and 2001 Trénel St.-Véran from Burgundy ($12.99). We tasted the wines first in pairs and then together as a group of four. After a few minutes of quietly sampling the wines, we had a short discussion and then ranked each pair according to personal preference.

In a tasting where all of the wines are a single varietal or style, it is common to taste all the wines and rank them from 1 to 8, according to preference or perceived quality. Since the different styles of whites and reds in this tasting are hard to compare with one another, I asked each person to pick a favorite from each pair.

It’s no surprise that opinions differed wildly from person to person. I was expecting the more familiar California wines to be favored, but that was not universally the case. The Honig Sauvignon Blanc was preferred over the Château Reynon Bordeaux Blanc, but both the Handley Chardonnay and Trénel white Burgundy had its share of admirers.

Follow with Reds

For the reds, we first tasted two Pinot Noirs: 2001 Elk Cove Willamette Valley from Oregon ($18) and Heresztyn Bourgogne Rouge from Burgundy ($16). (I could’ve substituted a California Pinot Noir for the Oregon one, but the Elk Cove seemed like the best West Coast Pinot from the store in the price range.) Then we finished with two Bordeaux style blends (wines based on Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot): 2000 Surh Luchtel Mosaique ($24) and 2000 Château Teynac St. Julien from Bordeaux ($19). The Oregon Pinot Noir was definitely the favorite, but the Bordeaux stood its own against its California counterpart.

Tasting a group of wines like this is a great opportunity for friends (new and old) to get together, with a built-in topic of conversation. Of course, after a few glasses of wine, people’s spirits are lifted and the conversation can go many directions. I selected a special bottle of wine from my cellar to enjoy after the main tasting – something a bit more complex than the relatively simple, inexpensive wines we’d tasted formally. It was a nice reminder that wine offers us all the opportunity to get together and enjoy our friends.

Editor’s note: This article is the second in a series on how to organize and host wine parties. The first article, in our March 2003 newsletter, discussed the types of wine parties and the basic procedures and considerations for any type. If you’d like to host a wine tasting similar to the one that Paul C. did – or something completely different – come talk to us. We’re eager to help you select the wines and provide pointers to help ensure that the party goes off well.

List of Wines Tasted

Here is a simple list of the wines we tasted:

Sauvignon Blancs

Chardonnays

Pinot Noirs

Bordeaux Blends (Cabernet Sauvignon / Merlot)

National Drink Wine Day (or President’s Day For Some)

HolidaysWhat will you be drinking this National Drink Wine Day? (Or as some others may refer to it as, “Presidents Day“). Whether you’re celebrating the day off with family or at home by yourself, we’ve selected a few wines that should make your day off a little more exciting. For this special holiday, we are showcasing some President’s “Day” Wines. Day Wines is led by Brianne Day, a natural wine producer who seeks to capture the essence of “place” in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

Silvershot Vineyards 2015 Pinot Noir

This Pinot Noir hails from the Eola-Amity Hills, the southernmost sub-appellation in the Willamette Valley. The nose is all decadence with aromas of strawberries and raspberries, but on the palate this wine shows real class and restraint. 2015 was the hottest vintage in recent Oregon history, and according winemaker Brianne Day, the vines in Silvershot actually had a stress reflex to the heat and lack of water- they stopped accumulating sugar- and that’s the reason why the wine has a lower 12% alcohol content. A delicious accompaniment to your President’s Day BBQ, or just your back porch. (available for $34)

Belle Pente Vineyard Chardonnay 2015

Cherry blossom, fresh cream, lemon, and nectarine. The stunning fruit here comes from “Belle Pente” (or “Beautiful Slope”), a site which truly embodies bio-diversity in the vineyard. The husband and wife team who care for the vines there also farm veggies, fruits, chickens, geese, and even cows! Brianne has crafted a pristine and head-turning Chardonnay with this bottling, reflective of the harmony and uniqueness of the site. (available for $38)

“Queen D” 2016

50% Marsanne, 25% Roussanne, and 25% Grenache Blanc, this is a clean and precise blend which showcases Brianne’s light and intuitive hand in the cellar. From Oregon’s rugged Applegate Valley appellation by the California border, this dry and subtlety stone-fruited wine is excellent with chicken, cheese boards, and seafood. (available for $23)

And to keep up with all the National Drink Wine Day news, make sure to follow the National Wine Day facebook page for more content.

Valentine’s Day Wines For Your Special Someone

HolidaysMake your Valentine’s Day complete with the perfect wine pairing. Below we have hand selected and tasted 8 bottles we believe will pair perfectly with a range of meals. Looking for some prepared meals to go with these great wines? We have also selected some pairings from Market Halls special Valentine’s Day menu that would go great with our wine selections.

Red Wines

Bourgogne, Pinot Noir

This village-level Pinot Noir is a fantastic value. Approachable and generous with its raspberry fruit and slight spiced note, it is enjoyable on its own and most certainly a versatile choice for chicken, pork, or game if you are cooking for your special someone.

Gevrey-Chambertin, Pinot Noir

This is an old-vine offering from one of Gevrey’s top producers. It greets the taster with aromas of ripe black cherries and red currants, followed by crushed rock, damp earth, and strawberries on the palate. A bold and traditional offering with good acid and length. Pairs perfectly with duck.

White Wines

Menetou-Salon, Sauvignon Blanc

Ephemeral orchard fruits, subtle yet supple with real limestone minerality. Great with any kind of seafood, vegetables, or salad, or just with a glass and a loved one…

Santa Cruz, Chardonnay

This cuvee is the epitome of richness and balance. Full-bodied, crisp golden apple and lemon chiffon on the nose, followed by vibrant acidity and a good weight on the palate. This is serious Santa Cruz Chardonnay that is grown, fermented, and bottled at 2,000 feet of elevation.

Rose Wines

Beaujolais, Gamay

Pretty, red fruits with a crisp clean close. Excellent and drinkable Valentines Day pink from Beaujolais!

Bandol, Mourvedre

With high aromatics of honeydew melon and white flowers, this Bandol is on the lighter side, and arguably the most elegant rosé that we have in the shop. Chin-chin!

Sparkling Wines

Sparkling Loire | Brut

This bottle of bubbles is pure delight. A blend of Chenin, Pinot Noir, and Chardonnay, we’re charmed by the atypical yet decadent aromas of Anjou pear and baking spices. This Loire sparkler is a little rich but has a clean, dry close.

Champagne | Extra-Brut

Based mainly on the 2013 vintage, but blended with 33% of reserve, this is a complex and finely-tuned champagne truly fit for a king or queen. The Jacquesson house has existed since

the 18th century, and remains today one of the most unique and high-quality producers in the region. The grapes achieve optimal ripeness and are only sourced from Grand or Premier Cru plots. This graceful bottle showcases flavors of star fruit and lemon curd, but it is the wine’s lithe acidity and palpable minerality that make it an exceptionally balanced and beautiful Champagne.

Market Hall Valentine’s Day Pairings

Market Hall Foods will be featuring a special Valentine’s Day menu, to compliment their updated menu, we have selected a Red and White that will compliment most of the menu.

White: Domain Pellé 2017 Menetou-Salon “Les Blanchais”

This Sauvignon Blanc hails from Menetou-Salon, an appellation adjacent to Sancerre. In this single-vineyard offering, we encounter subtle orchard fruit and herbaceous notes highlighted by limestone minerality.

Valentine’s Menu pairing: Crab Croquettes with Lemon Caper Aioli, Beet-Cured Salmon with Horseradish Crème Fraîche, or Mixed Chicories Salad with Citrus, Mint & Green Olives.

Red: Frederic Esmonin 2014 Gevrey Chambertin “Les Jouises” Vieilles Vignes

This wine, from one of Gevrey’s top producers, opens with aromas of black cherries and red currants, followed by earth, strawberries and wet stone on the palate. Bold and traditional with good acid and length, this middleweight old-vine Pinot Noir perfectly complements the earthiness of braised duck and mushrooms.

Valentine’s Menu pairing: Braised Duck Legs with Wild Mushrooms & Cipollini Onions.

Champagne & Caviar Pairings

Caviar: Tsar Nicolai “Classic” – $38

Pairing: Xavier Reverchon NV Brut – $27

This “Cremant” (which is a sparkling wine made in the same way as Champagne, but from a different region in France), is broad and rich. The wine shows very subtle fruit, with bass notes of salinity and minerality, complementing the light brine and fruitiness of Tsar Nicolai’s “Classic” caviar.

Caviar: Tsar Nicolai “Estate” – $64

Pairing: Jacques Lassaigne “Les Vignes de Montgueux” NV – $59

This Chardonnay-based Champagne has high-toned citrus and herbal notes, with plenty of acidity and brightness to complement the richer sea brine of the “Estate” level caviar, while the wine’s limestone minerality coaxes out its more subtle flavors.

Caviar: Tsar Nicolai Truffled Roe – $20

Pairing: Dehours & Fils “Terre de Meunier” – $53

This Champagne is made of a single grape variety, called “Meunier.” This is a grape which contributes body and richness to Champagne blends. In this Dehours bottling, extended lees contact provides toasted, brioche-like flavors that meld perfectly with the decadent and earthy flavor of truffles.

(Tasting notes by Heather Mills)

Excavating Alto Piemonte

PiemonteExcavation

artifact / ärdəfakt /

noun: an object made by a human being, typically an item of cultural or historical interest.

archeology / ärkēˈäləjē /

noun: the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains.

Experience

Wine can represent many things, like a particular flavor, a palatal experience, the time and efforts of cultivation, or the intellectual design of a product. And we can talk about it in so many ways too, evaluating wines geographically, aesthetically, linearly, horizontally. We use metaphor. We use qualitative biochemical data. We use narrative, and we attach it to a physical object destined for consumption, consume it, and begin to evaluate based on an array of potential methods of inquiry. If we are to treat the appreciation of wine in any academic way, that is to study it, we first must choose the method and scope of inquiry, which for me, particularly regarding older bottles, skews to the archeological.

Throughout my time at Paul Marcus Wines I was fortunate to taste, with some regularity, wines that far surpassed me in age and maturity. Over the past few years I’ve seen a surge in interest, enthusiasm, and availability of more obscure wines like this (18 year-old Sancerre Rouge, 28 year-old Portuguese Arinto, 30 year-old Santa Cruz Cabernet), wines that have taken on the secondary and tertiary characteristics of graceful development. Right away you can recognize acidity and color, defining characteristics of longevity, the ability to stay fresh, and the availability of concentrated fruit. But always, wines like these come with a caveat, a disclaimer of sorts about provenance, about transportation, storage, preservation, the guarantee on untainted products, the artifacts we so casually imbibe. So what can the study (and appreciation) of these agricultural remains signify about history? Perhaps that it inevitably devours itself.

Vineyard at Villa Era, Alto Piemonte

Visiting Piemonte

Last November, I was invited to Italy by the business consortium and viticultural association of Beilla, a small sub-region of the Alto Piemonte, west of Milan and almost to the Alps. It is an absolutely beautiful area, richin chestnuts, risotto, and an earnest wool milling industry. Right now, the region is in the process of redefining itself as a premium growing and production zone for grapes, particularly Nebbiolo. Today about 1,500 hectares of vines are planted in Alto Piemonte, primarily to Nebbiolo, though small amounts of Vespolina, Croatina, Uva Rara and Erbaluce are also planted. In 1900, however, over 40,000 hectares of grapes filled the region, a gross historical disparity which the winemakers there hope to resolve. The cool temperatures, extended sunlight exposure from altitude, latitude, and proximity to the Alps, and the geological event in which a volcano upended a mountain to expose ancient marine soils, all contribute to the severe minerality, acidity, and vivid coloration and red flavor of these Nebbiolo wines. Although the Langhe in the more southern part of Piedmont carries more commercial and critical weight in the industry now, the sheer volume of wine produced in the heyday of Alto Piemonte, and the evaluative quality of that wine, can shed light on both the cultural and natural history of the area. Touring vineyards and wineries, attending a seminar on soil types, tasting recent releases of wines from a dozen Alto Piemontese producers, and eating beautifully from the local farms and tables were all illuminating aspects of the culture and the cuisine and the heritage of the region, but nothing taught me more than tasting through a series of library bottles from four small wineries. It was easily the most personally revealing experience I’ve ever had with wine.

Before the tasting at Villa Era, a tiny producer in midst of laborious reclamation of vineyard sites from a century or so of forest encroachment, we toured the cellars (as we had the previous evening at Castello di Castellengo) to see the dusty, cobwebbed and moldy bottles of mismatched shape and size with tags and decomposing labels that date these artifacts through the past several centuries. These library collections of estate bottlings provide evidence that throughout time the properties yielded a product worth preserving in glass, underground in stable conditions, on the assumption that someday, someone would recognize that this was a fine wine designed to shine for future generations.

Bottles in the cellar at Villa Era, Alto Piemonte

Experiencing Aged Piemonte

The oldest artifact was a bottle of 1842 Castello di Montecavallo which is almost impossible to describe ingesting other than physical euphoria a, sensation of emotionally charged discovery. To share this piece of completely vibrant, assertive history, with the current generations of folks who farm the same land produced in me this neurological firing where I tried to connect pure sensory experience with the particular circumstance and somehow try to intellectually remember that this wine was deemed over the course of 175 years to be worth preserving, and that this gorgeous and completely unexpected semi-sweet but citric and lively wine five times my age was now going to be absorbed by my body. It felt as though I’d consumed an ephemeral dose of wisdom.

I know that’s hard to qualify. But trying to compare, or at least comprehend, the 1896 Castellengo and 1897 Villa Era was somewhat more grounded. I’d been in these cellars, walked in these vineyards; I was sitting in the building where 120 years earlier one of these wines had probably just finished fermenting, maybe just gone into barrel. One was reddish and slightly tannic, the other golden and slippery, and both were fresh. So you speculate. The grape, the vintage, the design? Two wines made a year apart within ten kilometers of each other and yet so fantastically different. And still with this surreal recognition that these wines were made around the time that my ancestors left Europe to participate in a different history a continent away.

Tasting a pair of wines, 1931 Montecavallo and 1934 Castellengo, I could sense some greater intensity, whether to do with process development or a renewed artisanal concentration in the wines after the industry fallout in the first decade of the 20th Century due to climate and disease, I don’t know. But the Montecavallo, like the 1842, offered a pure, sandy, pear-like quality, and the Castellengo, like the 1896, was denser, richer in color. The 1934 showed great definition as Nebbiolo, herbal, brilliant red, tannic and tough like a the skin of a wizened crabapple, a gorgeous wine and my favorite of the entire tasting.

Modern Respects

The more recent presentations, a 1960 from Villa Era, and a 1965 and 1970 from Tenuta Sella, a producer PMW has recently carried, proved a welcome familiarity, more within the bounds of my previous experience. These were wines with structure, ripe and dusty fruit and emphatic texture. These were wines wound with youth, wines that I expected to develop further. In the Sella wines, particularly, a continuously operating producer since the 17th Century, I tasted exuberance, a great and yet unrevealed potential. I felt aligned with Nebbiolo, a tart little corner of recognition on my palate, but I also felt the resonance of timbre, a uniformity, or at least a seam of connective tissue that stitched me to the place, to the people, to the things this circumstance in time and culture had revealed.

Tenuta Sella 1965 Lessona & 1970 Lessona

And then after sharing a bottle of the 2010 Sella Lessona over dinner back in California, and talking and laughing and telling the story, exposing the narrative and presenting the evidence, one can still only project the future. We have what we have and we have what has been preserved and with that we have to make do. I know that in Alto Piemonte they used to make great wine and that over time the wines changed and adapted and that now by looking back, it is also possible to look forward, to understand the history and prehistory of a specific place, the culture of past, present and future through artifacts.

(credit: Patrick Newson)

Champagne, Still Wines From A Sparkling Kingdom

ChampagneCoteaux Champenois

Drinking Champagne on a regular basis is something that is regrettably not all that common for many of us. It has a biased reputation for festive or special occasions only. Certainly, price understandably plays a factor here. But the region of Champagne itself, at least in my opinion, should be considered more often, even if you don’t want bubbles in your glass! It was, after all, originally a still wine producing region–and those wines still exist today.

The Coteaux Champenois is an appellation within the region which extends over hundreds of communes and produces excellent still wines. Today, a handful of producers continue the tradition of making both still reds, whites, and roses. For many producers, still wines are made for blending purposes into their sparkling wines. However, some decide to bottle their still wines, as is. Many find the red examples to be most compelling.

So why don’t we see more of these wines available in shops from one of the arguably greatest terroirs on the planet? Limited quantities, low demand, and a lack of marketing generally contribute to this; meanwhile, most of what is produced is simply consumed within the region itself. If you do have the opportunity, seek out these wines and the following producers, such as: Pierre Paillard, Paul Bara, and Jacques Lassaigne — to name a few.

As far as taste, the wines are high in acidity and light in body. This is no surprise since Champagne is known for its typically cold weather. One red we found especially compelling at the shop is Pierre Paillard’s 2012 Les Mignottes Bouzy Rouge for $53. It contains all Pinot Noir from Bouzy’s deep sedimentary soils. Bouzy may be known for its hard chalk soils but small amounts of sedimentary soils do exist, and are ideal for the grape. The wine is highly mineral-driven, fine, and detailed with extremely fresh cherry fruit. This wine is a true standout that any Champagne or Burgundy Pinot Noir fan should consider!

Exciting Older Bramaterra Riserva Vintages from Tenuta Monolo

Tenuta BramaterraThe Producer

I recently had the opportunity to taste several older vintages of Bramaterra Riservas from Umberto Dilodi of Tenuta Monolo, thanks to PortoVino importers. The tasting was held at the Kebabery in Oakland, and sure enough, Kebabs and aged Bramaterra Riservas are a stellar match!

The DOC of Bramaterra borders Gattinara and Lessona in Alto Piemonte. This particular DOC has a unique terroir in that it is less exposed to wind, coming predominantly from the north, and is composed of both volcanic and marine soils. Spanna (Nebbiolo), Vespolina, Croatina, and Uva Rara grapes are typically grown in the region. Since the climate here is cooler, the tannins of Spanna generally do not ripen to the same extent as its neighbors, and so instead it is often blended with the other grapes grown. As a result, the wines are known for their freshness, as well as balance and power.

More than likely though, Umberto’s wines haven’t shown up yet on your or other Piedmont enthusiasts radars, since they were never released to the market. In fact, Umberto made the decision to not sell his wines in order to avoid a conflict of interest while he was an integral part of elevating the region to its DOC status in the late 1970’s. Unfortunately, with Umberto’s passing, the winery operations came to an end. However, PortoVino has brought new life back to the winery by acquiring the entire cellar, and provides further insight into the winery below:

Origins

The Tenuta Monolo cantina was once part of a villa that contained over 40,000 volumes of manuscripts and books on philosophy, classical music (especially Baroque and Renaissance), and art. Surrounded by three-quarters of a hectare of vineyards, the villa was home to the eccentric musician Umberto Gilodi and his life-long friend, cellar-master, painter and engraver Orlando Cremonini.The two men lived a simple life. All farming was organic; Umberto Gilodi was a meticulous note-taker, and we have his documents that attest to not using pesticides or herbicides in a time when most in that area were. Fermentation was in large wooden botti with native yeasts. The vineyards, and so too probably the wines, were 60% Nebbiolo, 20% Croatina, 10% Vespolina, and 10% Uva Rara. The vineyard and cellar were followed by the famous Italian wine professor from Torino’s Enology School, Professor Italo Eynard.”

The Wines

2004 Bramaterra Riserva $49.00 (In-stock)

Supple and gentle on the palate, with a nice lift of acidity and good length. Great combination of tertiary aromas, including white pepper, cherry, and roses. Perfect to drink now.

2001 Bramaterra Riserva $70.00 (In-Stock)

More structure and tannin, and a bit more rustic in character, with predominately meaty, spicy, and floral notes.

1996 Bramaterra Riserva $66.00 (In-Stock)

My favorite based on its high acidity, fine tannins, and detailed spice notes. I particularly enjoyed its energy and precision.

1991 Bramaterra Riserva $66.00 (2018 Arrival)

The earthiest of the bunch, showing less floral character and more dusty mushroom and savory tomato notes. Also with less acidity than the ’96 so the wine is lovely and gentle on the palate. Do expect to find sediment, and as such we highly recommend decanting this wine.

1990 Bramaterra Riserva $56.00 (2018 Arrival)

Moving towards tertiary aromas and flavors. You will find rustic woodsy, wool, and meaty character on the nose, in addition to salty flavors. This wine expresses the vintage, which on the whole was a bit warmer, with a heartier and tannic palate. This would be outstanding paired with grilled steak or kebabs.

1985 Bramaterra Riserva $85.00 (In-Stock and Limited Quantities)

Absolutely lovely, lighter-bodied, and etherial. Quite simply a pleasure to drink.

The Perfect Rose to Cellar: Château Simone

FranceCellaring is a common practice for wine enthusiasts, whether for just a couple bottles or several hundred. But for those who do age their wines, how many hold on to dry rosé and drink it long after release? At the moment, the market for dry rosé is certainly “flowing.” Just last week in the shop Paul recollected how some years ago you had to really search to find a good rosé. Now, we are fortunate enough to find a wide range of excellent expressions in this category along with ample quantity. In fact, an entire section of the shop between the spring and summer months is entirely devoted to the “pink stuff”. However, although dry rosé is certainly acknowledged more often as a fine-wine category, with a wide range of price points to support, it is still not commonly cellared.

At the end of the day, rosé is primarily made to satisfy consumers’ desires for fresh and enjoyable sipping wine to drink during the warm weather months. Producers pick their grapes early, ferment at cooler temperatures in stainless steel, and avoid malolactic fermentation, in the hopes of give the market exactly what it wants—a charming, delicious, and crisp wine.

Nonetheless, there are several dry rosé bottlings currently carried in the shop that we can recommend cellaring; one in particular is truly a gem, and anything but basic. It is certainly worth seeking out and putting it to the test, well, in a few years!

Château Simone

Château Simone is located in the tiny appellation of Palette within Provence. Many are completely unaware of Palette due to its famous and much larger neighbors, Coteaux d’Aix en Provence and Côtes de Provence. The wines made at this 20 hectare property are unique to say the least with outstanding quality. The area is surrounded by a pine forest, the Arc River, and the Montagne Sainte-Victire mountain range. The vineyards sit on limestone soils at elevations as high as 750 feet, creating a microclimate with superb growing conditions. Some of the vines are as old as 100 years in age. For over two hundred years the Rougier family have run the Château, and are every bit as lovely as their wines.

Their rosé is produced in a similar fashion to their red wines and contains mostly Grenache and Mourvèdre with small amounts of Syrah, Carignan, Cinsault, Cabernet Sauvignon, Picpoul Noir, Muscat de Hambourg, Tibouren, Théoulier, and Manosquin. It is produced much like a red wine, moving from a wooden basket press to wooden vats for fermentation, along with one and a half to two years of aging in Foudres and another year in mature barrique. The dedication to this aging process gives this wine outstanding structure, power, and complexity that will certainly stand up to a decade of cellaring.

Domaine de Beudon

Wine VarietalsJacky Granges of Domaine de Beudon

Just last week we brought in two deliciously obscure wines from a tiny Swiss producer in Valais, which the importer alleges is accessible only by a dangerous-looking alpine gondola. Unfortunately, as I reached out for more information about these wines, I was alarmed to hear that Jacky Granges, the grower and winemaker who took over in 1971 and developed the vineyards to be fully biodynamic by 1992, had passed away in the short time between tasting his wines and their arrival at the shop.

Tragedy, however, makes them no less interesting or delicious. Instead, perhaps we can look on the brighter side and consider the liveliness of his wines as an opportunity to experience a small sliver of existence upon the mountaintop parcels of Domaine de Beudon, rife with medicinal herbs, livestock, and onsite hydroelectric power to create an oasis of grape-friendly agriculture.

Domaine de Beudon

The Wines

The notable absence of wooden barrels at Domaine de Beudon belied a depth of flavor and fine tannin that I usually associate with cold-climate, thin-skinned grapes like Pinot Noir and Gamay which comprise the majority of 2007 Vielles Vignes “Constellation” Valias Rouge. In addition, a small amount of Diolinor (an indigenous variety) is blended with the wine to give the bright bing-cherry flavors a bit more density. With the bottle age, indigenous yeast vinification, and cool, slow fermentation of grapes grown on granitic soil, a tough, rusty-ness holds the wine to the earth while the complex aromas slowly rise from the glass.

Similarly, the 2009 “Schiller” Valais Rose, which substitutes indigenous Fendant for the Diolinoir of the rouge, opens with a rich iron-like aroma, and continues through the palate with excellent acidity and fresh Rainier-cherry fruit intensity. Where the rouge is centered and earth-bound, the rose feels like a creaking swing set with enough lift and gravity to consider a full loop around.

Up and down with a tension born of high-altitude natural farming, the wines of Domaine de Beudon are excellent, but limited. We are fortunate to have these examples of artisan winemaking in our shop, and oh how far to slake this sacred thirst.

Voillot & Volnay: Article from Vintage 59 Imports

BourgogneThis morning I started off with the visit I was both most excited and most concerned about. Jean Pierre Charlot at Domaine Joseph Voillot in Volnay has been through the ringer more than anyone that I am slated to visit. The hail and small crops of previous vintages have impacted him more than most, and he’s also on the wrong end of the spectrum of those affected by this year’s frost.

Canvassing The Damage

Jean Pierre welcomed me into his office and we quickly overcame the fact that there wasn’t much middle ground on our language barrier. A brief chat and then we headed out to the vineyards for a survey of the damage. We go to Volnay 1er cru Champans and all is well. The growth looks great! It’s like nothing happened. Then we go to Volnay 1er cru Fremiets about 300km away and it’s a horror show. The vineyard is devastated.

More of the same as we visit his vineyards for village-level Volnay and Bourgogne rouge. Many vines are barren. Others have a small fraction of the normal growth. Some have produced a second bud, so on top of all the other challenges this frost has presented it also means that growers have to do two harvests one month apart. Think about all that additional work for the winemakers, yet for far less product. As rough as recent vintages have been for Jean Pierre this is the worst.

Voillot looks on in frustration at Fremiets Vineyard in Volnay

All told, these vineyards are down 90%. Jean Pierre has 9 hectares of vines in total and he’s lost about 7 hectares-worth in the frost. When you catch him in the moment you see his frustration and concern, and then he simply states it; all that work in the vineyard down the drain, and both his financial and mental fortitude have been pushed to the limit. But then he (more or less) shrugs it off, rhetorically asking “What can you do?” So we head back to the cellar.

The Cellar

The Voillot cellar is a thing of beauty. The mold covering the bottles is off the charts, but otherwise it’s orderly and clean…though clearly not as full as Jean Pierre would prefer. We dig into the 2015 barrel samples and I can safely make the blanket statement that these wines are a fantastic overall quality and express some serious terroir. I look forward to not just tasting, but drinking these wines over the next 20 or so years. These are the epitome of elegance and charm, and they exude a real sense of place. If you’re not yet familiar with these wines do yourself a favor and seek them out.

The harsh reality.

Other Bourgogne Travels

Following my visit with Jean Pierre I headed north for a photo tour of a number of grand crus in the Nuits. Chambertin Clos de Beze is a particular favorite, but it’s great to see all of these vineyards up close and in person. I eventually made it to the top portion of Clos des Lambraysfor a little lunch of leftover poulet de Bresse, cheese, bread and wine while I soaked in one of the better views I’ve come across so far. Late in the afternoon I visited with Domaine de Bellene in Beaune, which included another look at some 2015s in barrel.

The wines are in various stages of completion with some still working through malolactic and showing a bit of prickly CO2 on the palate, while others are already beautifully harmonious. Overall the whole Domaine operation is quite smaller than expected, and the conversation about running the negociant side of things is illuminating. Particularly the emphasis on slowly growing the options beyond the big name fruit sources of Gevrey, Meursault, etc., as those wines have gotten so expensive in recent years. The Saint-Romain blanc is a standout, as is the Saint-Aubin, an appellation that seems to be well represented on this trip so far.

We also had an interesting aside about premox, which the Domaine admittedly encountered in a couple of their wines a few years back. The consensus seems to be a stretch of time where winemakers emphasized a combo of too gentle a pressing, too little sulfur, too much battonage, and too much oak. Seems about right.

Time for me to hit the sack as I’ve got an early call in Gamay country tomorrow!

Rosé Season

Wine VarietalsEdmunds St. John – Bone Jolly Rose

Edmunds St. John Bone-Jolly Rosé

Featured in The New York Times

Congrats to local winemaker, Steve Edmunds for his recent accolades in the NYT article “20 Wines for Under $20: Spring Edition”. We are big fans of this excellent Gamay Rosé currently on our shelf for $23.00

“The wine stores tell us it’s rosé season (though in my opinion, it’s never not rosé season). Here is an old favorite, which year after year offers the vivacity characteristic of a good young rosé. It’s made entirely of Gamay Noir, the grape of Beaujolais (hence the somewhat awkward name Bone-Jolly), and it’s exactly what you want on those first few days out on the deck, the balcony or wherever you can grab space in the open air.” – NYT