Wine is love; from production to consumption.

Let’s get this out of the way quickly: For most of us, 2020 was a uniquely difficult and depressing year. To 2020, we say, good riddance.

And yet, 2020 was also a year in which small pleasures and simple delights took on a greater significance than ever before. Perhaps it was a book, a film, an album, a meal, or, yes, a bottle of wine–these tiny lifelines helped sustain us when we most needed it.

At Paul Marcus Wines, we sincerely hope you found your way through these trying times. With that in mind, we are happy to share with you our favorite wines of the year. Sure, it’s only wine. But these are the bottles that brought us just a bit of sunshine in an otherwise gloomy year.

A Personal Selection, A Personal Position (Polemic?)

After 25 years working in the wine business, I have found that I am drawn to wines that excite my intellectual interest, but also provide both visceral and emotional response. Wines that are natural, wines that are products of the land–farmed and raised accordingly. Though it is always true that ethics and responsibility in our daily choices are vital at all levels of societal interaction, it seems to me that they are especially important as we look back on 2020.

After 25 years working in the wine business, I have found that I am drawn to wines that excite my intellectual interest, but also provide both visceral and emotional response. Wines that are natural, wines that are products of the land–farmed and raised accordingly. Though it is always true that ethics and responsibility in our daily choices are vital at all levels of societal interaction, it seems to me that they are especially important as we look back on 2020.

So, in that spirit, to pick a single wine is, for me, impossible, and further not in line with my thinking at this juncture. So my favorite wine of the year is really my favorite producer of the year: Jean-François Ganevat. While I am always excited about his wines–no matter the region, variety, or blend–my subjective self is happily subsumed, though not lost, in the larger concern. I have tried to widen my perspective amid the concerns of the pandemic and worldwide racial and economic disparity.

Founded in 1650, Dom. Ganevat makes approximately 75 different wines, 57 of which are listed for sale at Kermit Lynch, Ganevat’s California importer. Furthermore, an unknown and perhaps unknowable number of additional cuvees do not make it out of France, and of the ones that do hit our shores, many with a 25 percent tariff, very few see the shelf. That said, we do have a few wines, about 15 or so–none of them, however, in any real quantity. But, wow, they are stupendously exciting. And delicious. Natural, yes, some include purchased fruit, but no matter if Jean-François is buying from similarly minded friends and neighbors.

Aside from being delicious, sensual wines, perhaps the greatest virtue of his wines is that so much is given to the drinker. It helps to be open-minded, to not go in expecting to find your absolute favorite wine. That is the way all “outdoor” wine works; we can’t always sell you your favorite wine. We all need variation. What I can tell you is that these are exactly what they should be, meaning no more than what was intended or hoped-for by M. Ganevat.

I only tasted with him once, around an old barrel in a deep cellar. He is kind, if overwhelmed with attention, and pours generously, and yes, it is difficult to keep them all straight. But it is certainly worth picking up a bottle or two–if you can find them!

–Chad Arnold

Island Charm

Patricia Perdomo’s eponymous wines are something to behold. At a scant 26 years of age, she already runs a bodega with her sister, Lucía, also a viticulturist and farmer. Their family has been growing vines in La Palma (Canary Islands) for generations, and, in my humble opinion, their knowledge of the land and its indigenous varieties certainly shows in the 2018 Perdomo ‘El Cantaro’ cuvee.

Patricia Perdomo’s eponymous wines are something to behold. At a scant 26 years of age, she already runs a bodega with her sister, Lucía, also a viticulturist and farmer. Their family has been growing vines in La Palma (Canary Islands) for generations, and, in my humble opinion, their knowledge of the land and its indigenous varieties certainly shows in the 2018 Perdomo ‘El Cantaro’ cuvee.

‘El Cantaro’ is a field blend of 35 percent listan negro, 30 percent listan prieto, 25 percent negramoll, and 10 percent albillo criollo. The 85-year-old vines grow at 3,600 feet of altitude on volcanic soils, where the high altitude and dry weather provide conditions hospitable to practicing organic viticulture. The wine itself is highly reductive, with some sanguine notes and gravity-defying black fruits. This is a wine of Burgundian finesse made by two sisters from a wild, rugged island off the coast of Africa. Only 100 cases were produced, and the containers just came in. Get some while you can.

–Heather Mills

Slice of Sicily

My favorite wine this year is like a breath of fresh air sailing off the Mediterranean waters, near Noto, in the southeastern corner of Sicily.

My favorite wine this year is like a breath of fresh air sailing off the Mediterranean waters, near Noto, in the southeastern corner of Sicily.

The 2019 Mortellito Bianco Sicilia Calaiancu is a young-vine blend of mainly grillo and a bit of catarratto, naturally fermented in stainless steel and aged for only six months in stainless as well. It has a rustic edge, as you might imagine, since the person who made it is what some might call “salt of the earth.” Think mandarin and lemon blossoms, coupled with pistachios, melons, and olives.

This wine reveals such an unexpected kaleidoscope of smells and flavors. It has a subtle richness, or perhaps, generosity, while at the same time having a nervy spine of refreshing acidity. The limestone-rich soils lend the wine a lifted minerality and moderate alcohol–thankfully, considering the warmth of the climate. Drink this with anything from fresh seafood to pizza–maybe a white anchovy pizza with marjoram or grilled swordfish with lemon–and let the wine shine!

–Jason Seely

Deep Balance

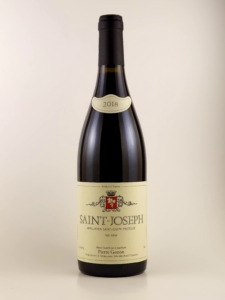

My most pleasurable wine memory from 2020 was courtesy of a syrah from Pierre Gonon, an iconic producer in France’s Rhone valley. The 2017 Gonon Saint-Joseph was delicious and compelling in aromatics, texturally lush and rich and lifted and tannic all at once. It was young and buoyant and simultaneously had that deep balance and structure that communicates it would age with great grace.

My most pleasurable wine memory from 2020 was courtesy of a syrah from Pierre Gonon, an iconic producer in France’s Rhone valley. The 2017 Gonon Saint-Joseph was delicious and compelling in aromatics, texturally lush and rich and lifted and tannic all at once. It was young and buoyant and simultaneously had that deep balance and structure that communicates it would age with great grace.

But what made it memorable was how much pleasure it brought to all four of us at the table. The white-wine drinkers were confused that they liked it so much; the big red drinkers were just blown away. Wine is better with company, and great wines really demand it. It makes me look forward to next year’s great bottles.

–David Gibson

Love in Lirac

Any favorite wine of mine must meet two very important requirements: high quality and reasonable price. Yes, I might greatly enjoy a bottle of Pommard or Barolo; however, if I cannot afford to drink a bottle of great Burgundy or Barolo on a regular basis, why should it be my favorite?

Any favorite wine of mine must meet two very important requirements: high quality and reasonable price. Yes, I might greatly enjoy a bottle of Pommard or Barolo; however, if I cannot afford to drink a bottle of great Burgundy or Barolo on a regular basis, why should it be my favorite?

As with every consumer good, the price of wine is not always delineated strictly by the quality of the product, but also depends on operating cost, R&D, and, of course, name recognition.

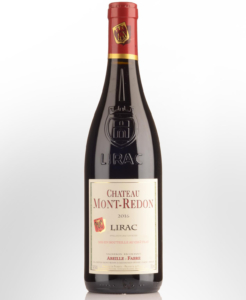

This brings me to Lirac, and the 2016 Château Mont-Redon Lirac. Everyone has heard of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, but how many have heard of Lirac? Although Lirac is less than seven miles away from Châteauneuf-du-Pape–with almost identical soil types and a similar climate–Lirac remains in the shadows. So if you are ever looking for a dense, earthy, and complex wine similar to Châteauneuf-du-Pape, but for half the price, look no further than Lirac.

This grenache-based wine begs for a steak pairing, with a fully tannic body that is powerful yet elegant, a medium nose that is dark and spicy, and subtle notes of blackberry and coffee. This is the perfect full-bodied yet unobtrusive wine to pair with a savory meal (or enjoy on a cold winter night). The oak influence gives the wine a smooth finish, with slight notes of vanilla. Best of all, it is drinkable this year! I recommend this bottle with a nice fat burger or rib-eye steak. It’s also quite enjoyable while watching a good movie by yourself, with the heater on.

–Hayden Dawkins

High in Chianti

Overshadowed by Montalcino and hampered by an outdated reputation, Chianti continues to fight back with a vengeance, consistently producing satisfying, versatile, relatively affordable wines. With Angela Fronti at the helm, Istine is at the forefront of Chianti’s renaissance.

Overshadowed by Montalcino and hampered by an outdated reputation, Chianti continues to fight back with a vengeance, consistently producing satisfying, versatile, relatively affordable wines. With Angela Fronti at the helm, Istine is at the forefront of Chianti’s renaissance.

Balanced, nuanced, graceful, and simply gorgeous, the 2016 Istine ‘Vigna Istine’ Chianti Classico is a single-vineyard sangiovese from a craggy, high-elevation (550 meters) plot in the forests outside of Radda. Fronti’s grandfather was in the business of vineyard construction, a business her family maintains today, but even her family had second thoughts about the four-hectare site, planted almost 20 years ago. Says importer Oliver McCrum, “Her brother told me that this vineyard site was so rocky and difficult to clear that they would have bailed on any other customer.”

The ‘Vigna Istine’ is fermented in a combination of stainless steel and concrete before spending about a year in large Slovenian oak. Vibrant, floral, herbaceous, and brightly red-fruited, with a freshness that belies its depth, this is a prized example of expressive, supple sangiovese, anchored by ample acidity and a gentle tannic embrace.

–Marc Greilsamer

Bouzy Rouge

My favorite wine discoveries are often the underdogs, the unsung, the undeservedly obscure, the outliers. And so it is for my favorite wine of this year: the 2015 Georges Remy Bouzy Rouge ‘Les Vaudayants.’

My favorite wine discoveries are often the underdogs, the unsung, the undeservedly obscure, the outliers. And so it is for my favorite wine of this year: the 2015 Georges Remy Bouzy Rouge ‘Les Vaudayants.’

Astute bubble-lovers will recognize Bouzy as a Grand Cru village in the Champagne sub-region of Montagne de Reims. Bouzy is famous for its pinot noir, most of which is made into Champagne. But luckily for us, the bouzillons (as locals are called) reserve a few bunches of their prized pinot for still wines. The formal appellation for un-bubbly wines made in Champagne is Coteaux Champenois (“slopes of Champagne”), but Bouzy Rouge is just so much more fun to say!

The wine is from a single parcel of organically farmed, 45-year-old vines. It’s aged for 21 months in used barrels and then bottled unfined and unfiltered. It’s elegant and even ethereal, while still having weight and presence on the palate. Imagine a vinous line drawn from the Côte de Beaune, through Marsannay, and then projected north a couple hundred kilometers to the latitude of Paris.

The 2015 vintage was exceptional in Champagne, as it was in Burgundy, and this wine now shows the benefit of several more years in bottle. The wine opens beautifully over time, so don’t rush it! Drink it over several hours, preferably in a Burgundy stem or other large wine glass, with duck, braised meats, or simply with gougères or a mild, semi-aged cheese. Then you, too, will be an honorary bouzillon.

–Mark Middlebrook

Cooperative Class

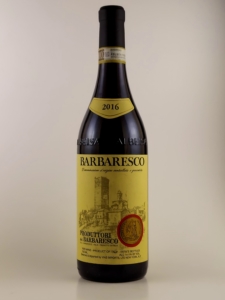

As the Italian buyer at PMW, I’ve made it a priority this year to recognize the brilliance of Barbaresco (in addition to its Barolo neighbor). I am pleased, therefore, to select the 2016 Barbaresco from Produttori del Barbaresco as my wine of the year. It is, pound for pound, price for quality, one of the greatest wines in the shop.

As the Italian buyer at PMW, I’ve made it a priority this year to recognize the brilliance of Barbaresco (in addition to its Barolo neighbor). I am pleased, therefore, to select the 2016 Barbaresco from Produttori del Barbaresco as my wine of the year. It is, pound for pound, price for quality, one of the greatest wines in the shop.

The Produttori is a venerable cooperative cantina with an important place in the history of the Langhe, dating back to 1894. The winery was forced to close during the fascist period of the 1930s, but managed to re-emerge in the postwar era. In 1958, the local priest helped restart production, with the first three vintages being made in the church basement across the old square where the Produttori stands today.

Nowadays, the Produttori enjoys a reputation as one of the very best producers in the region. If you are skeptical that a cooperative winery can achieve the heights of a great independent producer, these wines will quickly dispel that notion.

When Paul and I visited the Langhe a couple of years ago, we were excited to taste a good number of wines from the wonderful 2015 vintage, and they are indeed amazing. But we had several old-timers tell us that 2016 is the greatest vintage that they have ever experienced. The 2016 Barbaresco from Produttori certainly supports that contention. With beautiful fruit, and notes of cherry and anise, it is a lovely, inviting wine already. But it is also backed with a classic structure that will allow it to age gracefully for many years. Antonio Galloni, of the excellent publication Vinous, finished his laudatory review of the 2016 by saying simply, “What a wine!” I couldn’t agree more.

As an additional invitation, we would like to offer our customers a very special opportunity to check out the stunning 2015 Riserva Crus from the Produttori. The 2015 vintage is magnificent as well–so lush that they deliver immediate pleasure, yet capable of developing tremendous complexity over time. Through the month of January, PMW customers will receive 10 percent off of single bottles of these marvelous Crus and 15 percent off of six bottles or more. This will allow you to taste the Riserva wines for only a slightly higher price than the “normale.” Each Riserva is distinctive, and they are fascinating to compare and contrast.

(For more information about the various Crus, please visit the Produttori del Barbaresco website.)

–Joel Mullennix

Under the Volcano

My favorite wine of the year, the 2017 Monteleone Etna Rosso, comes from vineyards at the base of Sicily’s Mount Etna, on the north side at about 500 meters. The nose is beguiling; hard to define, but charming nonetheless. The nerello mascalese grape provides all the clean, earthy, mineral notes and red fruits of this light-colored wine, while a small amount of nerello cappuccio provides some depth to the hue. What I love about this wine is its vivacious life. The flavors sing on your palate; silky yet mildly gritty, it is an extremely versatile wine that matches well with duck.

My favorite wine of the year, the 2017 Monteleone Etna Rosso, comes from vineyards at the base of Sicily’s Mount Etna, on the north side at about 500 meters. The nose is beguiling; hard to define, but charming nonetheless. The nerello mascalese grape provides all the clean, earthy, mineral notes and red fruits of this light-colored wine, while a small amount of nerello cappuccio provides some depth to the hue. What I love about this wine is its vivacious life. The flavors sing on your palate; silky yet mildly gritty, it is an extremely versatile wine that matches well with duck.

Sadly, the 2017 vintage is gone, but luckily, we do have a few bottles of the single-vineyard ‘Qubba’ cuvee, which has plenty of years ahead of it. Beyond that, we look forward to the 2018 vintage.

–Paul Marcus

If you’d like to know more about any of these selections, please call or visit us at the shop. And don’t forget, our entire inventory is available online (for curbside pickup or shipping) at shop.paulmarcuswines.com.

Happy holidays from PMW, and please stay safe!

Celebrating Holidays: Bubbles for Valentine’s Day

HolidaysWhether you’re looking to enhance your Valentine’s Day dinner or simply toast with a loved one, Paul Marcus Wines has a range of sparkling wines from which to choose. Here are a few of our favorite bubbly bottles.

Portuguese native winegrower Filipa Pato and Belgian chef/sommelier/restaurateur William Wouters are both wife and husband and partners in wine in the central Portuguese region of Bairrada. This lovely sparkling rosé is a blend of local Bairrada varieties baga and bical (hence the name of the wine) made in the Traditional (i.e., Champagne) Method. It’s their Valentine to all of us: affordable, delicious, and bone dry.

Piemonte in Northwest Italy is not the first place that comes to mind for sparkling wines, but here we are: a creamy yet dry, easygoing yet distinctive spumante made from the rare local variety albarossa. Marvel at the sexy, pale-salmon color and the minimalist, elegant label–then pop, pour, and love.

For you kinkier couples, here’s an unfiltered, cloudy pétillant-naturel (fizzy from fermentation finishing in the bottle). If just saying “Blaufränkisch Pét Nat” gets your juices flowing, then this is the Valentine fizz for you. Electric-pink color. Juicy, yeasty, fruity, exuberant; the opposite of serious.

Here’s another romance-and-wine couple, carrying on their families’ traditions in the beautiful, pre-Alpine eastern French region of the Jura. Their sparkling rosé is 60 percent pinot noir along with 20 percent poulsard and 20 percent trousseau. It’s a bit darker in color and body than the other wines here–more for the (candlelit) dinner table than the pre-prandial couch. If you lusted over the Albert Finney/Susannah York eating scene in Tom Jones, then this may well be your Valentine wine.

Yes, this is the choice to really impress your Valentine–or simply to celebrate each other’s love of the best and of each other (not in that order, of course). It’s an all-pinot noir rosé from the aptly named Champagne village of Bouzy, in bubbly and elegant yet still hedonistic form. The wine tastes like the label looks: filigree and fine, opulent and impeccable, Grand Cru and gourmandise.

The Answer: Can I Find a Great Wine for Less than $50?

FAQSIf you stroll into Paul Marcus Wines with $100 to spend on a bottle, you will walk out with a stunning, perhaps even unforgettable wine. Most customers, of course, don’t have that kind of loot, but fear not. For less than $50, you can certainly find a memorable, first-class wine to savor and appreciate. Next time you need to put an exclamation point on a special occasion or simply satisfy a connoisseur’s high standards, consider these standout wines.

The standard-bearer in Rioja, Don Rafael López de Heredia first planted his famed, limestone-rich Tondonia vineyard on the River Ebro more than 100 years ago. This reserva spends about six years in large barrels, plus another handful in bottle before release. The 2007 version–75 percent tempranillo, 15 percent garnacha, and filled out by graciano and mazuelo–is a wine of both depth and subtlety, with finely honed tannins and pleasant notes of tobacco and spice. Aging potential of Tondonia wines is often measured in decades, not years.

There’s a certain charm you find in a Vouvray sec that is difficult to replicate–a balanced richness that seems unique to the chenin blanc of that appellation. Those in the know say that 2019 might be one of the best vintages this venerable producer has ever seen. This bottle is already capable of delivering immense pleasure–steely, stony, and energetic, with only hints of the opulence it will deliver over time. When that lush, waxy fruit comes to life over the next 10 years, watch out!

Considered in some circles to be the “Chablis of Sicily,” the Etna Bianco DOC, featuring the carricante grape, produces wines that are dry, racy, and mineral-driven. Russo’s Bianco uses only 70 percent carricante, rounded out by an assortment of Sicilian varieties. Aged on the lees in a combination of steel and wood, the result is textured and intense, yet bright, with a volcanic edge and luxuriously long finish.

There is something immediately gratifying about this sangiovese (mostly sangiovese, anyway, as this house, which dates back to 1846, still makes a point of adding a little dash of indigenous Tuscan grapes to the blend). This pretty riserva, which sees two years of oak, doesn’t try to do too much–the oak influence is understated, producing an appealingly red-fruited, medium-bodied wine that displays remarkable freshness and finesse.

Without a doubt, this is one of the best values we’ve found in the world of fine sherry. Although the VOS label indicates a 20-year sherry, its average age is probably closer to 30. What I love about this refined palo cortado is that, despite its long oxidative aging, it manages to retain more than just remnants of its former life as a manzanilla. There’s still a sharp, saline tanginess that perfectly complements the nutty, butterscotch elements. Get yourself some jamón Ibérico and Manchego cheese, and you’ll be in business. Or, after dinner, sip it as a “wine of contemplation.”

Reflections: Our Favorite Wines of 2020

NewsWine is love; from production to consumption.

Let’s get this out of the way quickly: For most of us, 2020 was a uniquely difficult and depressing year. To 2020, we say, good riddance.

And yet, 2020 was also a year in which small pleasures and simple delights took on a greater significance than ever before. Perhaps it was a book, a film, an album, a meal, or, yes, a bottle of wine–these tiny lifelines helped sustain us when we most needed it.

At Paul Marcus Wines, we sincerely hope you found your way through these trying times. With that in mind, we are happy to share with you our favorite wines of the year. Sure, it’s only wine. But these are the bottles that brought us just a bit of sunshine in an otherwise gloomy year.

A Personal Selection, A Personal Position (Polemic?)

So, in that spirit, to pick a single wine is, for me, impossible, and further not in line with my thinking at this juncture. So my favorite wine of the year is really my favorite producer of the year: Jean-François Ganevat. While I am always excited about his wines–no matter the region, variety, or blend–my subjective self is happily subsumed, though not lost, in the larger concern. I have tried to widen my perspective amid the concerns of the pandemic and worldwide racial and economic disparity.

Founded in 1650, Dom. Ganevat makes approximately 75 different wines, 57 of which are listed for sale at Kermit Lynch, Ganevat’s California importer. Furthermore, an unknown and perhaps unknowable number of additional cuvees do not make it out of France, and of the ones that do hit our shores, many with a 25 percent tariff, very few see the shelf. That said, we do have a few wines, about 15 or so–none of them, however, in any real quantity. But, wow, they are stupendously exciting. And delicious. Natural, yes, some include purchased fruit, but no matter if Jean-François is buying from similarly minded friends and neighbors.

Aside from being delicious, sensual wines, perhaps the greatest virtue of his wines is that so much is given to the drinker. It helps to be open-minded, to not go in expecting to find your absolute favorite wine. That is the way all “outdoor” wine works; we can’t always sell you your favorite wine. We all need variation. What I can tell you is that these are exactly what they should be, meaning no more than what was intended or hoped-for by M. Ganevat.

I only tasted with him once, around an old barrel in a deep cellar. He is kind, if overwhelmed with attention, and pours generously, and yes, it is difficult to keep them all straight. But it is certainly worth picking up a bottle or two–if you can find them!

–Chad Arnold

Island Charm

‘El Cantaro’ is a field blend of 35 percent listan negro, 30 percent listan prieto, 25 percent negramoll, and 10 percent albillo criollo. The 85-year-old vines grow at 3,600 feet of altitude on volcanic soils, where the high altitude and dry weather provide conditions hospitable to practicing organic viticulture. The wine itself is highly reductive, with some sanguine notes and gravity-defying black fruits. This is a wine of Burgundian finesse made by two sisters from a wild, rugged island off the coast of Africa. Only 100 cases were produced, and the containers just came in. Get some while you can.

–Heather Mills

Slice of Sicily

The 2019 Mortellito Bianco Sicilia Calaiancu is a young-vine blend of mainly grillo and a bit of catarratto, naturally fermented in stainless steel and aged for only six months in stainless as well. It has a rustic edge, as you might imagine, since the person who made it is what some might call “salt of the earth.” Think mandarin and lemon blossoms, coupled with pistachios, melons, and olives.

This wine reveals such an unexpected kaleidoscope of smells and flavors. It has a subtle richness, or perhaps, generosity, while at the same time having a nervy spine of refreshing acidity. The limestone-rich soils lend the wine a lifted minerality and moderate alcohol–thankfully, considering the warmth of the climate. Drink this with anything from fresh seafood to pizza–maybe a white anchovy pizza with marjoram or grilled swordfish with lemon–and let the wine shine!

–Jason Seely

Deep Balance

But what made it memorable was how much pleasure it brought to all four of us at the table. The white-wine drinkers were confused that they liked it so much; the big red drinkers were just blown away. Wine is better with company, and great wines really demand it. It makes me look forward to next year’s great bottles.

–David Gibson

Love in Lirac

As with every consumer good, the price of wine is not always delineated strictly by the quality of the product, but also depends on operating cost, R&D, and, of course, name recognition.

This brings me to Lirac, and the 2016 Château Mont-Redon Lirac. Everyone has heard of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, but how many have heard of Lirac? Although Lirac is less than seven miles away from Châteauneuf-du-Pape–with almost identical soil types and a similar climate–Lirac remains in the shadows. So if you are ever looking for a dense, earthy, and complex wine similar to Châteauneuf-du-Pape, but for half the price, look no further than Lirac.

This grenache-based wine begs for a steak pairing, with a fully tannic body that is powerful yet elegant, a medium nose that is dark and spicy, and subtle notes of blackberry and coffee. This is the perfect full-bodied yet unobtrusive wine to pair with a savory meal (or enjoy on a cold winter night). The oak influence gives the wine a smooth finish, with slight notes of vanilla. Best of all, it is drinkable this year! I recommend this bottle with a nice fat burger or rib-eye steak. It’s also quite enjoyable while watching a good movie by yourself, with the heater on.

–Hayden Dawkins

High in Chianti

Balanced, nuanced, graceful, and simply gorgeous, the 2016 Istine ‘Vigna Istine’ Chianti Classico is a single-vineyard sangiovese from a craggy, high-elevation (550 meters) plot in the forests outside of Radda. Fronti’s grandfather was in the business of vineyard construction, a business her family maintains today, but even her family had second thoughts about the four-hectare site, planted almost 20 years ago. Says importer Oliver McCrum, “Her brother told me that this vineyard site was so rocky and difficult to clear that they would have bailed on any other customer.”

The ‘Vigna Istine’ is fermented in a combination of stainless steel and concrete before spending about a year in large Slovenian oak. Vibrant, floral, herbaceous, and brightly red-fruited, with a freshness that belies its depth, this is a prized example of expressive, supple sangiovese, anchored by ample acidity and a gentle tannic embrace.

–Marc Greilsamer

Bouzy Rouge

Astute bubble-lovers will recognize Bouzy as a Grand Cru village in the Champagne sub-region of Montagne de Reims. Bouzy is famous for its pinot noir, most of which is made into Champagne. But luckily for us, the bouzillons (as locals are called) reserve a few bunches of their prized pinot for still wines. The formal appellation for un-bubbly wines made in Champagne is Coteaux Champenois (“slopes of Champagne”), but Bouzy Rouge is just so much more fun to say!

The wine is from a single parcel of organically farmed, 45-year-old vines. It’s aged for 21 months in used barrels and then bottled unfined and unfiltered. It’s elegant and even ethereal, while still having weight and presence on the palate. Imagine a vinous line drawn from the Côte de Beaune, through Marsannay, and then projected north a couple hundred kilometers to the latitude of Paris.

The 2015 vintage was exceptional in Champagne, as it was in Burgundy, and this wine now shows the benefit of several more years in bottle. The wine opens beautifully over time, so don’t rush it! Drink it over several hours, preferably in a Burgundy stem or other large wine glass, with duck, braised meats, or simply with gougères or a mild, semi-aged cheese. Then you, too, will be an honorary bouzillon.

–Mark Middlebrook

Cooperative Class

The Produttori is a venerable cooperative cantina with an important place in the history of the Langhe, dating back to 1894. The winery was forced to close during the fascist period of the 1930s, but managed to re-emerge in the postwar era. In 1958, the local priest helped restart production, with the first three vintages being made in the church basement across the old square where the Produttori stands today.

Nowadays, the Produttori enjoys a reputation as one of the very best producers in the region. If you are skeptical that a cooperative winery can achieve the heights of a great independent producer, these wines will quickly dispel that notion.

When Paul and I visited the Langhe a couple of years ago, we were excited to taste a good number of wines from the wonderful 2015 vintage, and they are indeed amazing. But we had several old-timers tell us that 2016 is the greatest vintage that they have ever experienced. The 2016 Barbaresco from Produttori certainly supports that contention. With beautiful fruit, and notes of cherry and anise, it is a lovely, inviting wine already. But it is also backed with a classic structure that will allow it to age gracefully for many years. Antonio Galloni, of the excellent publication Vinous, finished his laudatory review of the 2016 by saying simply, “What a wine!” I couldn’t agree more.

As an additional invitation, we would like to offer our customers a very special opportunity to check out the stunning 2015 Riserva Crus from the Produttori. The 2015 vintage is magnificent as well–so lush that they deliver immediate pleasure, yet capable of developing tremendous complexity over time. Through the month of January, PMW customers will receive 10 percent off of single bottles of these marvelous Crus and 15 percent off of six bottles or more. This will allow you to taste the Riserva wines for only a slightly higher price than the “normale.” Each Riserva is distinctive, and they are fascinating to compare and contrast.

(For more information about the various Crus, please visit the Produttori del Barbaresco website.)

–Joel Mullennix

Under the Volcano

Sadly, the 2017 vintage is gone, but luckily, we do have a few bottles of the single-vineyard ‘Qubba’ cuvee, which has plenty of years ahead of it. Beyond that, we look forward to the 2018 vintage.

–Paul Marcus

If you’d like to know more about any of these selections, please call or visit us at the shop. And don’t forget, our entire inventory is available online (for curbside pickup or shipping) at shop.paulmarcuswines.com.

Happy holidays from PMW, and please stay safe!

Thanksgiving Small-Pod Three-Packs

HolidaysThe Answer: What’s the Purpose of Bottle Capsules?

FAQSWhile browsing around our shop, you might notice some bottles of wine do not utilize a capsule, while others have a simple black capsule or a decorative, colorful capsule. A few bottles might even boast a wax seal. Does it make a difference?

Why do producers use capsules?

Capsules are the metallic or plastic wrapping you’ll find around the neck of the bottle–the enclosure that you remove with a knife or foil cutter before popping the cork. The presumed purpose of this capsule is to protect the cork during storage from such things as insects, rodents, and mold. Capsules also help identify wines while stored horizontally.

If you’ve ever searched for a bottle of Champagne or Burgundy in our shop, you’ll notice most producers have very specific capsules that stand out from one another. In addition, they can also protect the label from wine drippings when the bottle is poured. Capsules were most commonly made from lead before the 1980s; today they are usually made from aluminum, plastic, or tin.

What does a wax seal indicate?

Some producers use a wax seal instead of metallic or plastic. While a wax seal is mostly for aesthetics, it can also aid in preserving the freshness of a wine. While a metallic capsule will protect a cork from damage, it does not affect the ability for oxygen to transfer between inside and outside the bottle. A wax capsule is mostly air tight, eliminating oxygen transfer (similar to a screw cap).

Due to the lack of oxygen transfer, it can be hypothesised that wax seals will reduce the ageability of a wine, although I was not able to find any definitive experiments on this. Below, however, is an image showing the aging progression of a wine using 14 different types of cork/caps. Note how the far left bottle, with a screw cap, has barely changed over the course of 10 years.

Variance in aging of wines with different corks. (source: Australian Wine Research Institute)

Why would a producer decide to exclude a capsule?

Well, there isn’t a single answer, but it usually comes down to cost efficiency, elimination of waste, and aging capability. If a producer is making a wine that is intended to be enjoyed young, there is no need to account for storage, and chances of the cork becoming damaged are low. So if you find a bottle of wine without a capsule, this is usually an indication the wine should be opened in the near term. Eliminating the cost of producing all of those capsules can potentially allow the producer to reduce the price of the wine–and it is a more environmentally friendly approach as well.

Various Capsules

Does the lack of a capsule affect the quality of a wine?

Nope! As mentioned above, the use of a capsule nowadays is mostly for aesthetics and has a minimal effect on the wine. When you find a bottle of wine without a capsule, it will often come from a smaller producer, or possibly a more eco-conscious producer trying to reduce its footprint. Whatever the rationale, you can be assured the quality of the wine is not dependent on the use of a capsule.

Reflections: Memory, Wine, and Language: Some Personal Thoughts, Part II

NewsYou can read Part I of this essay here.

Intimacy

I think we need intimacy every day. For me that happens when I hold my wife’s hand, even for a moment when we cross the street, or when my daughter curls up with me and asks me to read to her. I feel close to the world when I read a good poem or when I have a great glass of wine–when metaphor or image lets me in on my own life.

How We Know Where We Are

I remember the day we did nothing

but walk down Willow Glen Road

through fields of Queen Anne’s lace

and lavender thistle toward a pond

quietly leaking its algae scents

to the air. Two wagon wheels rolled

with rust are repaired by their place

in some history, details so smooth

that missing spokes speak like vertebrae.

A stone carriage house holds these

memories like fixed stars, ghosts

of a yellowed cosmology, the first

chapter in a book where the sky

supports the handmade walls, where

rainwater collects easily, puddling

the soft earth. This could be the day

your father said he was leaving ––be back

soon, he said, and you knew it didn’t

matter because you would always remember

how the smoke poured from his mouth

as he spoke, and ferried his words

across the great body of water between

you. It could have been any evening

somewhere in Pennsylvania when your son

asked if he could visit the stars, reach

out and grab hold, needing the moonlight,

it seemed, more than you ever had.

Somewhere near the center of every memory

is a single flower, forgotten in the scrapbook

your grandmother asks you to open

each time she stays. It could have been

any day when nothing special happened,

when children sat in the sun-baked streets

popping tar bubbles, celebrating the solstice,

the friendships that spiraled by the poolside,

the summer air thick with mosquitoes

and no-see-ums circling every gesture.

These have all slipped under the folds

of another calendar when some days

got circled in red ink to remember flowers

picked along backroads, constellations

thrown into place by stories we will

tell our children, and your eyes, impossible

to imagine without the context of these galaxies.

Partial

The glottal stop is not a word but is part of speech. The invisible is in us.

Life’s not a paragraph.

Quotidian Religion

The simple things are at the center. They are signposts, and remind us with every sip that flavor interacts with feeling. When the curl of ferrous sulphate in the rosato rises, or the pinch of spice in the Chinon takes us back to our backyards. The deep well of a Meursault takes us back to our gardens, to the roses, the losses, our fingers sticky with pine. Each bottle of wine, like each friendship, connects us to our lives. The simple things hold.

The Picture

There is this picture my uncle Hank took in April 1975 at Newark Airport. There’s a 707 in the air. It’s about 250 feet off the ground and rising. My mom and brother are on the plane with me. My dad had died two months earlier. We are on our way to Florida to see Walt Disney World. The picture proves he existed. As liftoff is proof of gravity.

The old, grainy, black-and-white picture is beautiful, but you can’t see me on the aisle of row 22, my hands gripping the arm of the seat. At times we’re all invisible. It’s not that my uncle captured us in the picture so much as he captured us in time. Maybe we all have more control than we think. He held his brother a last time and for all time, though this is harder for us to see.

There are so many disappearances. I disappeared first into the plane, then into the cloud, and then into the crowd at the recently opened Orlando International Airport, and finally back to our house on Taylor Road with a different family.

*

When my mother died, I flew back to New Jersey to clean out the house where I grew up. I was surprised to find the picture––surprised I’d kept it. One evening, with the smell of cleaning solutions in every room, I was sitting at the dining room table alone. I sat looking from the picture to the woods in our backyard, and back to the picture. The woods, in their waving, I now saw, had hidden so much.

How We Protect Each Other

I close my eyes

to crimson explosions

to remember watching you

plant iris bulbs

in the wormed soil,

your wife at the sink

rubbing gently the crystal

of your wristwatch

like a coin––

where the rubbing

was a few words

whispered secretly,

saying how much it meant

that you were out there

arranging the earth

before the next rain.

Only connect.

It is, after all, the conversation under the fig tree. The figuring out, the pursuing of:

( ) or ( ) ( ) or ( ) and ( )

Chemistry

The Problem of Describing Trees

Of Films & Memories

In 1971, Pauline Kael reviewed The French Connection, starring Gene Hackman (maybe the only actor to have been in every film ever made), and in her review she says, “There’s nothing in the movie (for me) you can enjoy thinking over afterward” ––I think wine reviews that invoke that thinking will benefit wine drinkers everywhere.

*

My uncle Don died this morning.

Tradition

In the opening credits of the 1994 film Star Trek: Generations, starring both Patrick Stewart and William Shatner, we follow, as the names appear in some Hollywood sequence, an unopened bottle of Dom Perignon, Vintage 2265, as it tumbles through deep space to crash on the USS Enterprise NCC-1701-B.

There is much clapping inside the ship when the bottle explodes—and the ship doesn’t.

You can see them raise their glasses. Begin to talk…

After Work

I’m sure the stained-glass makers laughed

as they made mistake after mistake. Tracing

the cartoon while only occasionally looking

up. Trying to stay within the lines. All the

curves. An arm only later, clearly too large,

after the lead had cooled. A chest that could

in no human way support all that light. An

extra leg, a joke, noticed just before the evening

meal. The father, after the long day, telling

how the day went. The stories he took home.

Variations from the Word. The spiral of

blue where the earth should have continued.

The children still washing and laughing.

Repeating the variations, and for the first time

knowing the story is not so much a window

as it is a panel of light. As it is a story.

You can read Part I of this essay here.

Regional Roundup: The Dry White Wines of Hungary, Part II: Somló, Hajós-Baja, Mátra, Badacsony

Hungary, UncategorizedLast month, I wrote about dry wines (and one sweet ringer) from Tokaj, in northeast Hungary. This month, we’ll fan out into other Hungarian wine regions and explore more of the dazzling plethora of characterful indigenous grapes, wine regions (many of them, like Tokaj, with volcanic soils), and small, family-run producers.

Most Hungarian white wines offer some body and texture, along with prominent acidity and minerality. They’re also low in alcohol; all but one of the wines presented here are under 13 percent. Don’t let the unfamiliar words on the labels scare you off: I’ve included some pronunciation guidance below, and in any case, the proof is in the glass. If you love French, Italian, Iberian, and higher-acid domestic white wines, these wines will expand your horizons and add a new dimension to your meals (or Zoom happy hours).

The Hungarian wine appellations mentioned in this article (plus Tokaj, from last month’s article).

2013 Fekete Béla Somló Hárslevelű ($23)

Somló (SHOWM-low) is a wine appellation in western Hungary, not too far from the border with Austria–a low volcanic mountain rising out of the plain. Fekete Béla is by local acclaim the “Grand Old Man” of the appellation. This very wine is the last vintage that he made before retiring in his 90s. Hárslevelű (harsh-LEV-el-oo) is the grape variety, a genetic offspring of furmint that’s more aromatic and a little softer in structure.

This wine is aged in large Hungarian oak casks for two years before bottling. The nose is a festival of dried herbs, with some dried flowers playing supporting roles. There are lots of texture and body, plus a hint of sweetness, with just enough balancing acidity and a whisper of bitterness. Those who like aged Sancerre will enjoy this. And how often do you get to drink seven-year-old Hárslevelű?! Try it with herb-y pizza or pasta sauce, or just on its own at the end of a meal, maybe with an herb-crusted semi-aged cheese. (13.5 percent alcohol)

2017 Sziegl Pince Hajós-Baja Olaszrizling Birtokbor ($22)

Hajós-Baja (HI-yosh-BYE-uh) is located in southern Hungary, near Serbia. Olaszrizling (OH-loss-reez-ling), called welschriesling or riesling italico in other countries, has no genetic relationship to true riesling. It’s widely planted throughout Eastern Europe and the most widely planted white variety in Hungary. The Sziegl family started their winery in 2012, with husband Balázs in the vineyards and wife Petra running the cellar and making the wine–a new generation following the old Hungarian custom of men working in the vineyards and women running the cellars. (Pince (PEEN-sa) means cellar; it’s a word you see frequently on Hungarian labels.)

Their olaszrizling is bright, mineral, and slightly herbal, with medium body and mouthwatering acidity. It leans more toward grüner veltliner than toward riesling. GV fans, among others, should check it out. Drink it with all of those green things that you’re inclined to eat with grüner veltliner or sauvignon blanc: artichokes, green beans, basil, arugula pesto… (12.5 percent alcohol)

2018 Losonci Mátra Riesling [skin contact] ($22)

This winery, run by Bálint Losonci (low-SHOWN-see), is in the volcanic appellation of Mátra, in north-central Hungary, between Budapest and Tokaj. He and a few other likeminded small producers are rehabilitating the reputation of Mátra from decades of Communist-era industrial farming and winemaking. Bálint farms organically and works naturally in the cellar, favoring skin contact for the white wines, no filtering, and only minimal SO2 addition at bottling. All of the wines benefit from naturally high acidity due to the crazy mix of volcanic, iron-rich clay, and chalky soils in the vineyards.

This wine is true riesling–not olaszrizling—but utterly unlike any you’ve had, thanks to the soils and a week of skin contact. It’s the other end of the spectrum from a Mosel (German) riesling: spicy, smoky, redolent, textured, and powerful, yet still without overt weight or alcohol, and of course completely dry. If you love riesling, you need to try this wine–and if you don’t, you probably should try it, too, because it’s so atypical. Smoked oysters, spring rolls, kolbasz (the Hungarian version of kielbasa), and barbecue all leap to mind. My wife and I also enjoyed it with a bunch of Vietnamese dishes from Tay Ho in downtown Oakland–yes, that’s a plug. (12.5 percent alcohol)

2017 VáliBor Badacsony Kéknyelű ($32)

Kéknyelű (cake-NYAY-loo) is the grape variety, of which there are 41 hectares (100 acres) in existence, all of them in Badacsony (BOD-ah-chah-nya), a region on the northern shores of Lake Balaton in western Hungary. The producer, Péter Váli, has the perfect description of this wine: “It tastes like frosted basalt rocks.” There’s a smoky, flinty minerality. It’s textural, but with knife-edge acidity. This is a special wine; it’s age-worthy, and also drinking great now. Chablis drinkers will love it–and it offers Premier Cru quality at a Village-level price. Think oysters, Petrale sole, and shrimp risotto. (12 percent alcohol)

2018 Losonci Mátra Pinot Gris [skin contact] ($23)

Here’s another skin-contact white (or, more properly, gray/gris/grigio) from Bálint Losonci in Mátra. Three weeks of skin contact give a medium rosé color and extravagantly spicy nose with minerals, rocks, and baking spices. Aficionados of skin-contact white wines, step right up: This is your (dry) jam. There’s some tannin, so pair it with proteins: Meats (pork, chicken, tacos al pastor) and hard cheeses work well. Or, if you like a gentle tannic twang unadulterated, go for it. (12.5 percent alcohol)

Many thanks to Eric Danch of Danch & Granger Selections, the importer and distributor of all of these wines, for his help with this article.

Reflections: Memory, Wine, and Language: Some Personal Thoughts, Part I

NewsI’ve been thinking about what to say during the pandemic when someone walks into the shop and asks what wine they should drink with dinner.

Something different, I say, as “different” seems to describe most of our lives right now, and I think most of us want something different because we want at least that consistency.

The Central Paradox

It seems to me that we are sharing the experience of the pandemic, but we often feel alone. So open that bottle of Pommard, Gevrey-Chambertin, or Barolo you’ve been saving and sit on your porch–if the Air Quality Index allows–and open it. Say hello to the neighbors you didn’t know you had.

I’ve been thinking about what words to use to tell you…

…that the wine you drink today will chart more than your future. That each bottle you drink and think about will give you more language. That you’ll be able to talk about Rothko and the Faiyum mummy portraits.

Pavane

Every glass is a shape, a still life, a piece of music, the curl of green in the tree outside your window. The last plum.

What Do We Really Want to Talk About When We Talk About Wine?

We want, it nearly always seems, to talk about love or the garden. Or the moon dervishing in her scarves.

Say…

…you’re at my house for a dinner party. We’re on the deck. It’s about 7:15, and the Champagne is, sadly, though not tragically, nearly gone. And while everyone is enjoying it, some of us are sort-of-secretly hoping a brave soul will socially distance the bottle and save the remaining third until we’ve had time to try the trousseau. Surely, the Champagne will taste different after a glass of snappy fall-fruit red from the Jura.

…you’re at my house for a dinner party. We’re on the deck. It’s about 7:15, and the Champagne is, sadly, though not tragically, nearly gone. And while everyone is enjoying it, some of us are sort-of-secretly hoping a brave soul will socially distance the bottle and save the remaining third until we’ve had time to try the trousseau. Surely, the Champagne will taste different after a glass of snappy fall-fruit red from the Jura.

I never want to get in the way of anyone’s enjoyment, but too often we don’t try out new ideas, or revisit old convictions. Making alterations in our accepted patterns seems especially important during these times because we might find better solutions or even see problems for the first time.

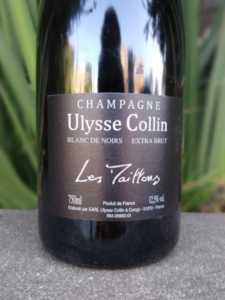

So why not save the Champagne for a while and see how it goes with the entrée? Or–open a bottle of Ulysse Collin’s Blanc de Noirs ‘Les Maillons’ Extra Brut NV Champagne to go with that piece of grilled rib eye.

Explanations (i)

The drinker is part of the wine. Q. E. D.

Explanations (ii)

We tell ourselves stories because we need to follow a narrative to make sense of the weeks; we tell ourselves stories because we need to lie to ourselves to deal with the pandemic, the fires, the inevitable shifts in our country’s foreign and domestic policies.

since feeling is first

We want, it so often seems, to say what we’re thinking. It takes practice to articulate what our bodies want.

A Lakeside Cabin

All worthwhile subjects exist in part and in paradox.

The less we understand about a subject, the longer the conversation can be about that subject. That’s a good thing. We want to talk about things we want to understand more about, like wine, cosmology, or the price of furniture–though the letter involves rickety logic. Each bottle is its own story, its own beginning, seemingly isolated but sipped along the same shore, our toes trailing the cold clear water.

Explanations (iii)

We are at times only essence.

Two Concepts to Help You Learn About Wine

What We’re After, After All

An accurate application of language to experience. Something new, perhaps? A glass of kadarka or jacquere? Lamb chops at 1:00 AM?

[Stay tuned for Part II of this essay, coming next month.]

Regional Roundup: The Dry White Wines of Hungary, Part I: Tokaj

Hungary, UncategorizedVinum Regum, Rex Vinorum (“Wine of Kings, King of Wines”) was the famously enthusiastic pronouncement by King Louis XV as he proffered a glass of Hungarian Tokaji to Madame de Pompadour, the official chief mistress of his court. (Yes, that was a real position in Ancien Régime France.) Louis and his main squeeze were enjoying a sweet wine in the mid-18th century. Though traditional Tokaji remains among the noblest sweet wines in the world, the habits and attention of most of us–noble, bourgeois, and plebs alike–have turned to dry wines.

Luckily for us, modern Hungary is here to help, with a dazzling plethora of characterful indigenous grapes. The white wines tend to have some body and texture, along with prominent acidity and minerality. They’re also low-alcohol; all of the wines presented here are under 13 percent. The words on the labels may be unfamiliar and a little challenging to pronounce, but don’t let that scare you off. With a wide array of wine regions (many of them with volcanic soils) and small, family-run producers, Hungary offers so much to discover and enjoy for those of us who love French, Italian, Iberian, and domestic white wines.

This month, we’ll discuss white wines from Tokaj (TOKE-eye), in northeast Hungary, with a little chunk of Slovakia. (Tokaj is the name of the region; Tokaji is the wine from that region.) Next month, we’ll cover white wines from four other Hungarian wine regions.

Bodrog is the main river running through Tokaj, and Borműhely (bor-MEW-hay) means “wine workshop.” This wine, made with 70 percent furmint and 30 percent hárslevelű (Tokaj’s two most important grapes), is organically farmed, then fermented and aged in stainless steel. Salty, high acid, and fully dry, with some texture, it’s utterly delicious and an outrageous deal for an organic wine of this quality and character. If you enjoy fresh, young Loire Valley chenin blanc, give this a try. Drink it with clams, chicken, or something spicy, or even as an aperitif if you like something with a little body. (12.5 percent alcohol)

This wine is all furmint, the most noble variety in Hungary and the backbone of most Tokaji, whether dry or sweet. Tokaj native Sarolta Bárdos created this family winery in 1999, and her vineyards are also certified organic. She is among the new generation leading the quality renaissance in Tokaj and part of a long tradition of woman winemakers in Hungary (where the men historically worked in the vineyards, and the women ran the cellars).

This wine comes from the single vineyard Barakonyi, which has been officially recognized as first-class (premier cru, more or less) since 1737. Fermentation and aging are done in Hungarian oak barrels. It delivers pear-like, slightly honeyed fruit with an almost icy minerality and a hint of oak. There’s texture, elegance, purity, and length; those who enjoy white Burgundy or restrained California chardonnay will like this a lot. (Plus, where are you going to find one of those from a premier cru vineyard for $24?!) Drink it with richer fish and poultry dishes, pork, and spicy enchiladas. (12.9 percent alcohol)

Here’s another 100 percent furmint dry Tokaji, this one from the equally storied, first-class Öreg Király Dűlő (Old King Vineyard). It’s the highest-altitude, steepest, and most distinctly terraced vineyard in Tokaj. The several extra years in the bottle give you the opportunity to see how dry Tokaji ages. Winemaker Vivien Újvári, yet another woman in charge of a Hungarian cellar, uses organic farming and minimalist winemaking techniques, aging her wines in larger Hungarian oak barrels.

This wine is beautifully expressive and vibrant now, with a more smoky minerality and a saltier, quite savory palate. If Tokaj Nobilis Barakonyi echoes some of the qualities of white Burgundy, the analog for Barta Öreg Király Dűlő might be aged Loire chenin blanc. It’s a perfect accompaniment for white meats and game birds of all species, smoked salmon, and Asian dishes without too much sweetness. (12.7 percent alcohol)

OK, this is an article about dry Hungarian white wines, but it would be a dereliction of vinous duty not to mention our one sweet wine from Hungary: Tokaji Aszú. (Vinum Regum, Rex Vinorum!) It’s an aristocratically hedonistic and spectacularly delicious nectar made in part from individual berries (mostly furmint, plus in this case some hárslevelű and other local grapes zéta and kövérszőlő) affected by botrytis, a so-called “noble rot” that shrivels, concentrates, and transforms the flavor of the grapes. You’ll find notes of dried fruits, especially stone fruits, along with a thousand other flavors, fruit and otherwise.

There’s no need to analogize here, because Tokaji Aszú is simply the greatest dessert wine in the world (sorry, Sauternes). It will sing with blue cheeses, chocolate, and even potato chips. (The last pairing is my invention, as far as I can tell. Try it with José Andrés potato chips, made by San Nicasio in Andalucía, Spain, and available at Market Hall Foods.) Or simply have this Tokaji Aszú on its own as a very special way to end a meal, perhaps with some dried apricots. (11.5 percent alcohol)

Many thanks to Eric Danch of Danch & Granger Selections, the importer and distributor of all of these wines, for his help with this article.

Why We Love: The Sicilian Way

SicilyThere is something very unassuming about the intricacies of Sicily, given its vast, arid landscape, rustic way of life, and history as a cultural crossroads. The people of this island, situated at Italy’s southern tip, take enormous pride in the simple and beautiful treasures that the land has to offer.

View overlooking Cefalù

It is hard to find another place that has been impacted by such a wide array of cultural influences: Phoenicians, Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Romans, Spanish, British, and French among them. Over time, these influences have helped spawn some of Italy’s most cherished agricultural products. Their olive oils, from several different parts of the island, are regarded as some of the finest around. World-class chocolates hail from Modica, and Sicilian nuts are highly prized as well, especially the pistachio, hazelnut, and pine nut (actually a seed). Of course, the wines of Sicily are no exception.

Mount Etna, located in the northeast, is an active volcano that is home to a diverse range of vineyards, some of them planted as high as 1,000 meters up the slopes. These infertile basalt soils are rich in magnesium and iron, which provide little organic matter for the vines. This produces low yields and higher-quality grapes.

The red nerello mascalese grape is king in this region, exhibiting characteristics of both nebbiolo and pinot noir, while typically boasting some serious structure and rusticity. Carricante is the focus of mineral-driven Etna Bianco, while catarratto, inzolia, minella bianca, grecanico, chardonnay, and other local varieties are sometimes called on to round out the blend. At Paul Marcus Wines, we’re fortunate to work with some of Etna’s most esteemed producers, including Girolamo Russo, Terre Nere, Benanti, and Graci.

The Val di Noto, in the island’s southeastern region, is home to some of my absolute favorite wines on the planet. Vittoria is famous for its blend of frappato and nero d’avola, called Cerasuolo di Vittoria. These wines can offer an amazing balance of freshness, aromatic complexity, and red-toned earthiness that just screams “Sicilia.”

*****

In the late spring of 2017, my family and I traveled to this uniquely gorgeous locale. So much of the island feels as though you’ve stepped back in time–at least a generation, if not two or three.

I still remember our stay above the picturesque northern coastal town of Cefalù, where we floated in the serene waters of the Mediterranean with our young daughter. (I could really go for that right about now.) The Arab-Norman cathedral in the town square is a real jaw-dropper, too. I also recall spending a late afternoon, bleeding into early evening, on our rooftop terrace in Ortigia, sipping Graci’s Etna Bianco and Russo’s Etna Rosato all the while.

One of my fondest memories was our visit to winemaker Ciro Biondi in Trecastagni, a small town on the southeast side of Mount Etna–an absolute gem of an experience. It was a hot day, not too uncommon in these parts, and we slowly navigated our way up the narrow roads. When we finally arrived, Ciro greeted us with such warmth and took us on a walk to the vineyard just above his house.

The house was once a palmento–these were traditional winemaking structures, usually just one big room or so, that housed the area for the grapes to be received from the vineyards, then pressed and gravity-fed into its next vessel (concrete, wood, or terracotta). We spent an hour or two tasting a few of his wines on his patio, complete with outdoor kitchen, in the middle of his vineyard. He took us back down to his house and made us pasta for lunch–noodles made from local grains, breadcrumbs, a bit of garlic, fennel fronds, and lots of Etna olive oil.

Just a few humble ingredients of the utmost quality to make a dish shine: the true Sicilian way.